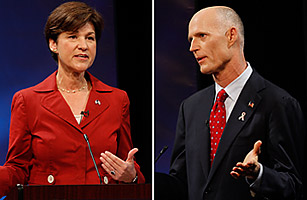

Alex Sink, left, the Democratic candidate for Governor, debates Rick Scott, the Republican candidate, at the Nova University in Davie, Fla., on Oct. 20, 2010

When the 2010 U.S. Census is tallied, Florida is expected to pass New York as the nation's third largest state, behind California and Texas. That makes its Nov. 2 gubernatorial race between Democrat Alex Sink and Republican Rick Scott all the more important — and all the more unsettling, given the nagging and widespread uncertainties about whether either candidate is really up to the task of running this economically battered peninsula. Sink, 62, is Florida's chief financial officer and a former bank president; Scott, 57, is a veteran CEO who once ran the world's largest hospital corporation. Yet when asked during their nationally televised debate on CNN Monday night, Oct. 25, what Florida's minimum hourly wage is, both got it wrong. (It's $7.25; they each said $7.55.)

While making many Floridians wish current Governor Charlie Crist hadn't decided to run for the U.S. Senate this year, Sink and Scott have spent an inordinate amount of time — and, at least in Scott's case, obscene sums of money — slinging mud at each other. But that was probably inevitable. Scott, who resigned in disgrace as CEO of the Columbia-HCA hospital corporation in 1997 when it was fined a record $1.7 billion for Medicare fraud, has a large and legitimate attack-ad target on his back. "He is somebody we just can't trust, because he doesn't follow the rules," Sink said Monday night. That's compelled Scott to counterpunch with any dirt he can dig up on Sink, like his charge that since 2007, when she took office as CFO, Sink ignored warnings about risky investments and presided over the loss of $24 billion from the state's $140 billion pension fund. "You failed as a fiscal watchdog," Scott told her.

Independent campaign watchdogs say Scott's pension-fund accusation is largely exaggerated. (It's fallen only $8 billion in real value.) Still, despite the fact that Sink has more government experience than Scott — who has none — their race is a dead heat, with the two alternating as the front runner in polls and just a few points separating them. Scott, a conservative Tea Party darling from Naples, in southwest Florida, has spent $50 million of his personal $218 million fortune (and an additional $11 million from his wife), raising fears even inside his party that he's trying to buy the Tallahassee governor's mansion. Sink, who is from Thonotosassa, near Tampa, is herself a millionaire; the former Florida president of what is now Bank of America has spent about $10 million (most of it from campaign contributions). Combined, it's the most expensive gubernatorial election in Florida history by far.

Which is why it's especially disappointing to watch Sink and Scott, in face-offs like the CNN debate, working harder to slam the other's character than to explain their platforms. (Sink got caught in her own rules-breaking Monday night when she took a debate-coaching text message from an aide during a commercial break.) The Sunshine State is clouded these days by record unemployment and the country's second highest home-foreclosure rate. Sink, a moderate Democrat, insisted that since she proposes small-business tax cuts to jump-start the economy, Scott "can't put the 'Obama liberal' label on me." But while the state expects a $2.5 billion budget shortfall next year, Sink was vague about how she'd accommodate the education-spending increases she wants and which low-wage Florida desperately needs.

Scott, meanwhile, wants to cut property taxes 19% and eliminate Florida's business tax altogether. He said Monday that he'd pay for it the Tea Party way: by chainsawing government bureaucracy and regulations. But aside from repeatedly chanting that President Obama's health care reform bill is "horrible for patients and taxpayers" — Scott heads the nonprofit Conservatives for Patients' Rights, which opposes the reform — he too was short on specifics.

Scott, a lawyer and former Navy radarman who made his fortune acquiring hospitals in Texas, is also disturbingly short on explanations for the Columbia-HCA scandal. Though the company admitted to massive Medicare fraud, the worst in U.S. history, Scott was never personally charged. And while he says he takes responsibility, he insists he knew nothing about the bogus lab tests, falsified patient bills and doctor kickbacks. The catch-22 for Scott is that not knowing about such widespread malfeasance in his midst looks just as bad to many voters as knowing about it. He hardly reassured those skeptics in Monday's debate when he said, "You surround yourself with the smartest people you can, and you trust them. That's what I did [at Columbia-HCA], and that's what I'll do as governor."

In any other election year, a statement that brazenly clueless could cost a candidate the race. So could refusing, as Scott's done, to release testimony he gave at a deposition this year (in a lawsuit since settled out of court) involving a doctor's accusation that Scott's new health care facility firm, Solantic, also submitted false information. Or balking, as he's done, at sitting down with any of Florida's newspaper editorial boards.

But this is the angry year of the "outsider," and this is the state of Florida: both a time and a place in which things often don't make much sense. Given the state's large Latino population and reliance on tourism, not even alpha conservatives like former governor Jeb Bush would take Scott's stands on immigration (Scott favors Arizona's draconian anti-illegal-immigration law) and oil drilling off the Florida coast (Scott's for it). Nevertheless, Scott may well win next week. If he doesn't, Sink's election would make her Florida's first female governor. But given Scott's controversial past and freespending campaign, his election could set a precedent as well.