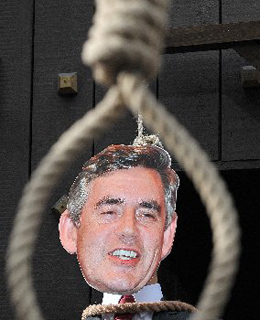

A mannequin depicting Prime Minister Gordon Brown is pictured to illustrate a hung parliament

To many voters and politicians, the prospect of a hung parliament is nothing short of an electoral nightmare. A hung parliament is one in which no party has an overall majority, which means no party has more than half of the MPs in the House of Commons. An absolute majority requires one party to win 326 seats: in simple math terms, the Labour Party, which currently has 349 seats, would lose its absolute majority if it shed 24 seats; the Conservatives would win an absolute majority by gaining 116 seats; while the Liberal Democrats need 264 more seats for a majority. Any other outcome will result in a hung parliament.

The doomsayers point to 1974, the last time this scenario played out in Britain. While the governing Conservatives, led by Ted Heath, earned the most votes, Harold Wilson's Labour party ended up with the most seats, which is the most important barometer of success. Heath chose not to resign; instead he spent what Wilson called the "longest dirty weekend" trying, and failing, to agree to a coalition with Jeremy Thorpe's Liberal Party to stay in power. (Heath resigned the following week, resulting in Wilson eventually forming a minority government, which limped along until a second election that same year, where he won a tiny overall majority.)

All signs this time point to a hung parliament, or a small Tory majority. "We suspect the Tories are going to come first in seats, but they're probably not going to make a majority," says Professor Curtice at the University of Strathclyde. "If no one party has more than 280 seats, it would mean the Liberal Democrats clearly have the balance of power and therefore as a result there would have to be some understanding between the Liberal Democrats and either the Conservatives or Labour."