Twenty years ago, it seemed unlikely that black and white South Africans could avoid a cataclysmic struggle. How did we manage to turn back from the precipice and join one another in the long walk to a nonracial democracy?

There were many factors — but one of the most important was the role played by Nelson Mandela, who was then serving a life sentence in prison. By the mid-'80s, while still in prison, Mandela had concluded that there would be no winners if the country continued to slide into conflict. Without the knowledge of the exiled African National Congress leadership, he entered into a discreet dialogue with the South African government—which was reaching a similar conclusion. He later succeeded in convincing suspicious comrades of the need for a negotiated solution.

After his release from prison in 1990, Mandela played a decisive role in negotiations that led to our first democratic election. During the talks, he and I often clashed—particularly with regard to the violence that threatened to undermine the process. Nevertheless, when the occasion demanded it, we were able to join hands to keep the talks on track.

After his inauguration as President in May 1994, Mandela won the affection and respect of South Africans of all races for the manner in which he promoted reconciliation. In a memorable gesture, he pulled on a Springbok rugby jersey — previously associated with whites-only teams — after South Africa's fairy-tale victory in the 1995 rugby world cup. Since retiring as President in 1999, he has continued to play an important role as senior statesman, gently and skillfully probing his party's line on troubling issues such as AIDS and Zimbabwe.

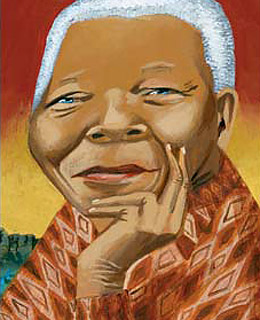

Mandela, 86, was born into a leading Xhosa family and was destined to become a royal adviser. Although history dictated a far greater role for him, he has throughout his career manifested the unmistakable grace and authority of a natural aristocrat.

De Klerk was President of South Africa from 1989-94