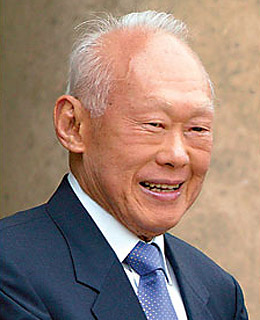

Lee Kuan Yew leaves the impression of someone constrained, like a large man in a tight suit. As Prime Minister of Singapore, he has built a rich little city-state where everything seems to hum like a well-oiled machine: orderly, efficiently and above all predictably, with no room for noisome dissent. Although Lee, 81, stepped down as Prime Minister, he can still fine-tune his social model as Senior Minister. The quality of his "digits," as he once called citizens of his city-state, might yet be improved through social engineering: careful marriages, good breeding, cultivated deference to the most shining digits. Lee has turned his nation into a kind of boarding school, where strict conformism is the only route to prosperity.

One feels, though, that Lee would have liked to have had a larger stage on which to project his vision — hence, perhaps, his tireless lecturing of other world leaders. Because Singapore is too small to shape the future of the world, Lee's mark on history would have to be as a kind of Asian philosopher king. One of the last proponents of social Darwinism, Lee believes that politics is, among other things, an unending struggle for racial fitness. None of this is strikingly original, but Singapore's technocracy provides an appealing model of modern success, combining economic drive with social discipline, free-market capitalism with political authoritarianism. China's post-Maoist leaders would love to create a giant Singapore. Is it possible to achieve with 1 billion Chinese? What's more, is it desirable?

Buruma is a Henry Luce Professor at Bard College in New York

From the Archive

In Defense of Asian Values: In a TIME interview, Singapore's Lee Kuan Yew reflects on China and the Asian economic crisis