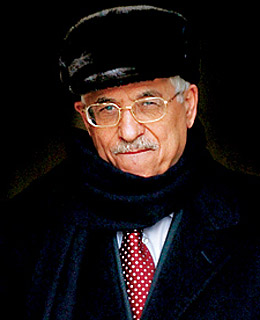

Mahmoud Abbas—also known as Abu Mazen—is a man of civility and wry humor. Throughout the Oslo peace process, when I served as the U.S. Middle East special envoy, he and I had our own code for communicating where things stood. When I asked how he was, if he said, "Not bad," it meant things were not good. His "Not bads" were usually followed by a chuckle—as if to say, O.K., it isn't good, but we will make it better.

Abu Mazen, a long-time Palestinian activist, has consistently been against violence. He once told me the only responsibility the Palestinians had was to provide Israel security, and if they did, Palestinian needs would be met. He is neither defensive about Palestinian aspirations nor willing to betray the Palestinian cause. But for as long as I have known him, he has seen coexistence with Israel as an essential Palestinian interest, not a favor to Israel.

Unlike Yasser Arafat, his predecessor as chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization, Abu Mazen, 70, has never craved power. He believes in sharing it and creating a rule of law. But that won't be an easy process. His political faction, Fatah, is divided. And the Palestinian Authority he now heads is deeply resented for corruption. To succeed, Abu Mazen must act decisively. He must strike against corruption. He must show that life can get better for Palestinians citizens. And he must stop the violence.

Abu Mazen's strategy for ending the killing involves co-opting—not confronting—the groups most responsible for terrorism (Hamas, Islamic Jihad, al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades). For now, they will go along with him. But if the public does not see a payoff soon, those groups will perceive little risk in violating the cease-fire. Abu Mazen is in a race against time, and we had better do our part to help him win.

Ross is a counselor at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy and the author of The Missing Peace

From the Archive

Escaping Arafat's Shadow