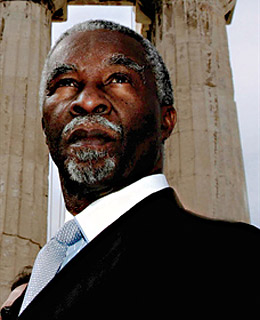

South African President Thabo Mbeki can be so busy putting out fires around Africa that South Africans sometimes sneer that he has too little time for his own country. Such is the burden of the most powerful man in Africa, the first person local and international leaders call at the slightest hint of trouble, and the one African influential enough to strong-arm rival factions into cease-fires and sometimes even peace deals. French President Jacques Chirac discovered the extent of Mbeki's mojo last February when rival parties in the troubled former French colony Ivory Coast told him that they trust the South African more than any Western leader. So incensed was Chirac that Mbeki was muscling in on former French territory that he publicly advised Mbeki that he should "understand the soul of West Africa" before setting out to broker peace deals there.

If there is one thing Mbeki understands, it's Africa. When the erudite, Web-surfing former exile took the mantle from South Africa's first black President, Nelson Mandela, in 1999, most, including Mbeki himself, wondered how he would ever fill Mandela's shoes. Six years on, and having led his ruling African National Congress party to an increased majority in elections last year, Mbeki, 62, is proving a powerful leader in his own right. If Mandela helped unite a divided nation, Mbeki has set out to achieve something almost as difficult: to drag Africa into the international spotlight and spark an "African Renaissance" that will bring democracy, peace and development. Mbeki's views on aids have been less welcome: he has questioned the link between the hiv virus and aids. But his proposal for an African Marshall Plan has the support of heavyweights like Britain's Tony Blair. And his constant efforts to keep Africa on the agenda helped move the G-8 industrial nations to start work on a joint plan with Africa to boost the continent's development.

South African journalist Gumede is the author of Thabo Mbeki and the Battle for the Soul of the ANC