Viewing Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey in the year 2010 is a depressing experience. According to this 1968 movie, by now we were supposed to have moon colonies and regular passenger service on space planes. And anyone who struggles with automated receptionist messages or programmable televisions knows that today's computers are just as psychotic as HAL 9000, only dumber.

We like to believe we live in an era of unprecedented change: technological innovation is proceeding at a rate with no parallel in all of human history. The information revolution and globalization are radically disruptive. Just as Barack Obama would like to be a transformational President, so the rest of us like the idea that we live in a thrilling epoch of transformation. But the truth is that we are living in a period of stagnation.

Surprisingly, this stasis is most evident in an area where we assume we are way ahead of our predecessors: technology. In fact, the gadgets of the information age have had nothing like the transformative effects on life and industry that indoor electric lighting, refrigerators, electric and natural gas ovens and indoor plumbing produced in the early to mid-20th century. Is the combination of a phone, video screen and keyboard really as revolutionary as the original telephone, the original television set or the original typewriter was?

Genuinely revolutionary technological innovations are rare, and when they appear, there is a long time lag before they begin to transform the economy and daily life. The steam engine was used for nearly a century to pump water from British mines before it was successfully applied to manufacturing and transportation. The gasoline-powered car was invented in the 1880s, but mass automobile use had to wait until the 1920s in the U.S. and the 1950s and '60s in Europe and Japan. There was a similar delay between the invention of the computer and the microprocessor and the widespread adoption of the PC in the 1990s and 2000s. Even if there are dramatic breakthroughs in nanotech or biotech tomorrow, we may not enjoy the benefits for decades, or generations.

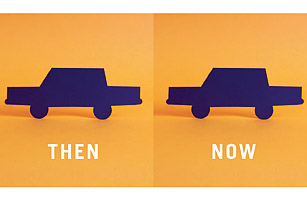

Technology has been remarkably stagnant in the areas of transportation and energy. As energy expert Vaclav Smil has pointed out, global jet transportation relies on the gas turbine, which was developed in the 1930s, and global shipping uses the diesel engine, invented in the 1890s. The fastest commercial airliners ever to fly reside in museums. The most cost-effective forms of mass transit everywhere, except for a few dense urban areas, are buses and planes.

Whether the heat source is coal, natural gas or nuclear energy, most electricity today is generated by a variant of the steam turbine that has been around since the 1880s. The wind turbine and the solar-thermal and photovoltaic technologies beloved by greens are old enough to qualify for Social Security. And these elderly technologies are limited to those privileged enough to live in industrialized countries. A substantial minority of the human race still derives heat and warmth from wood and dung.