Political borders remain among the most fundamental obstacles to human progress around the world. And yet while a borderless world could be a great thing, we can't assume it into being. We have to actually build it. Nothing would make a greater contribution toward removing justifications for armed conflict and toward economic development. In the next decade, drawing a new map of the world won't be just a worthy goal, it will become a moral, economic and strategic imperative.

The notion of a borderless world seems chimerical. Even in a globalized age, 90% of the world's people will never leave the country in which they were born. For them, borders still matter greatly — and even violently. From the Israeli-Palestinian "fence" to the U.S.-Mexican border, demarcating, monitoring and defending borders is still the big business of the military-industrial complex.

And yet, because we've been so focused on the inviolability of borders, we've neglected the fact that many of the very entities borders supposedly define were collapsing from within. Dozens of postcolonial states, from Congo to Pakistan, either don't really have or don't even deserve meaningful borders with their neighbors. And this has made long-standing dilemmas virtually intractable.

Take the Middle East. Decades of diplomatic bickering and White House Rose Garden ceremonies haven't delivered Mideast stability, but an understanding about infrastructure might. One obstacle to the realization of a Palestinian state is the fact that the West Bank and the Gaza Strip are not connected. Investing in an arc of roads and commuter-rail lines linking the West Bank and Gaza — in addition to building modern air and seaports — would help a Palestinian state eventually sustain itself. Independence without infrastructure is futile.

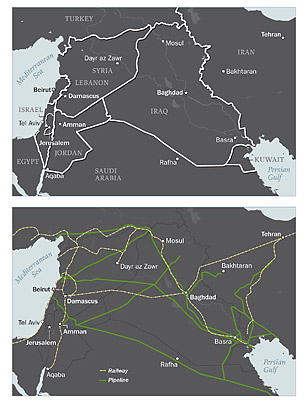

The Kurds know this, which is why they have been signing oil-exploration agreements with companies from Canada to Norway in preparation for the day the entity known as Iraq officially ceases to exist. If we replaced all the post-Ottoman political borders on our maps with lines representing the region's oil pipelines, we'd have a much more accurate picture of the vectors of influence and interdependence — and potential avenues for creating peace. Kurdistan would, after all, be landlocked; it has no choice but to get along with its neighbors if it wants to get the oil out.

Similarly, why do we lazily accept the continuing existence of Sudan, a British colonial construct joining Arab Muslims and African Christians in Africa's second largest country, a place so large that three disconnected civil wars — in Darfur, South Sudan and the east — are raging at the same time? A more stable and peaceful arrangement for Sudan would be to focus on independence for Darfur and South Sudan sooner rather than later, allowing them to rebuild themselves as smaller states at peace with their neighbors instead of facing Khartoum's persistent and nefarious undermining from within.

Beyond Sudan, Africa would benefit hugely from a reimagining of its current borders. Some innovative transborder ideas have emerged, such as sharing hydropower projects in the Great Lakes region or even establishing transboundary conservation parks, as South Africa is doing with its neighbors. Africa can become economically viable only if its plethora of puny economies merge from more than 50 into just a few.

Leaders seeking to respond to the global economic and underemployment crises should take a lesson from the world's most successful instance of a subordination of arbitrary borders: the European Union. The E.U. is the world's most peaceful multinational zone and its largest economic bloc, combining 27 countries, 450 million people and a $20 trillion GDP. The solution to the hundreds of lines that scar our political geography is to physically build the lines that connect people across them. If we spend just 10% of what we do on fighting over and defending borders on transcending them, the next decade — and the decades beyond — will be better than the last.

Khanna is the author of The Second World: How Emerging Powers Are Redefining Global Competition in the 21st Century (Random House, 2009)