"We have all been bystanders to geno-cide," Samantha Power wrote in the opening of her 2002 book, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. "The crucial question is why." Combining archival research with her own reporting from the killing fields of Rwanda and Bosnia, Power, a former freelance journalist and war correspondent, and a graduate of Harvard Law School, set out to explain why the U.S., at the height of its power, failed to stop the major genocides of the 20th century. Power's study examined U.S. responses to such horrors as the Ottoman massacre of the Armenians, the Nazi Holocaust, the crimes of Pol Pot and Saddam Hussein's gassing of the Kurds. In each case, Power argued, U.S. policymakers "did almost nothing to deter the crime." During atrocities like Saddam's slaughter of the Kurds and the Hutu killing of 800,000 Tutsi in Rwanda, the U.S.'s refusal to intervene emboldened the killers even more.

What made Power's argument so bracing — and cemented its place as one of the past decade's most important books on U.S. foreign policy — was her verdict that, far from ignoring genocide, three generations of American leaders knowingly and deliberately decided it was not in the country's interest to stop it. "One of the most important conclusions I have reached," Power wrote, "is that the U.S. record is not one of failure. It is one of success ... U.S. officials worked the system and the system worked."

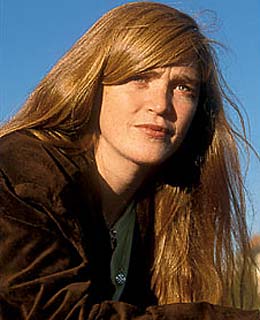

A Problem from Hell won the Pulitzer Prize and made Power, an Irish-born 33-year-old who is the executive director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard, the new conscience of the U.S. foreign-policy establishment. Though she worked as an adviser to former Democratic presidential candidate Wesley Clark, Power has a nuanced philosophy that is not an easy fit with either party. She condemns the first Bush Administration for not committing military force to stop Iraqi genocide before and after the first Gulf War. But she opposed the second Gulf War. "My criterion for military intervention — with a strong preference for multilateral intervention — is an immediate threat of large-scale loss of life," she has said. "That's a standard that would have been met in Iraq in 1988 but wasn't in 2003."