Fighting infection and developing heart disease don't seem at first to have much in common. Microbes, after all, attack from the outside in, whereas a heart attack is an inside-out job, a gradual gumming up of the body's plumbing system with cholesterol until blood flow to the heart almost comes to a standstill.

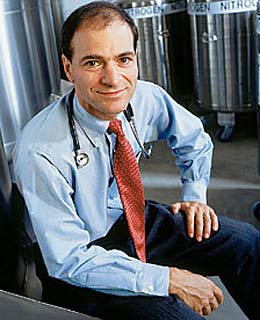

At least that's what doctors used to think. But Dr. Paul Ridker has changed that and the way doctors treat heart disease. A cardiologist at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, he has spent the past decade exposing an alliance between the infection-fighting immune system and heart disease that could finally explain one of the biggest health puzzles in recent decades: If cholesterol is such a major contributor to the nation's No. 1 killer, why do half of all heart attacks occur in people with normal cholesterol levels?

The answer, it turns out, involves inflammation. As the body's first line of defense against invading bugs, it's the reason that cuts swell and turn red as immune cells flood in to attack the microbes. Fat, when it builds up in plaques inside heart vessels, can launch the same type of alert, causing the plaques to rupture and lead to a heart attack. Ridker exploited this response by measuring inflammation with a specific marker of the process, C-reactive protein (CRP). CRP is easily picked up in the blood and reliably indicates how much inflammation is occurring in the heart — and thus how likely a heart attack might be.

Ridker's first encounters with disease came early on; his family spent two years in New Delhi, where he made a painful and personal acquaintance with parasite after parasite. Before getting his medical degree from Harvard, he spent a year in sub-Saharan Africa, treating patients in Kenya, Zambia and Zimbabwe just as the AIDS epidemic was emerging. "My experiences overseas gave me the idea that you could use a very different toolbox to tackle the heart-disease problem," says Ridker.

While researchers agree that CRP is a strong predictor of heart disease, they are still conducting studies to prove that reducing CRP levels can actually cut heart-disease risk. Ridker has shown that statins, the cholesterol-lowering drugs, work as anti-inflammatory agents as well, hitting heart disease with a one-two punch. Even more exciting are new trials showing that the inflammatory response may play a role in other conditions, such as Alzheimer's disease and cancer. After decades undercover, inflammation's role may finally be out in the open.

From the Archive

The Fires Within: Inflammation is the body's first defense against infection, TIME looks at when it goes awry