In 1996, Roger Ebert called Peter Jackson's The Frighteners "a film that looks more like a demo reel than a movie—like the kind of audition tape a special-effects expert would put together, hoping to impress a producer enough to give him a real job." Ebert couldn't have known how right he was. For in making the film, Jackson had amassed a gigaload of effects technology. He just needed the right subject in which to put his cybertoys to spectacular use.

The subject, we know, was the Middle-earth wars. J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings books handed Jackson a quest story involving dozens of exotic species and hundreds of dreamlike or infernal settings. Over a seven-year stretch in his native New Zealand, Jackson brought this vast canvas to life, later earning nearly $3 billion in movie theaters and oodles more on home formats. He blended live action and computer animation in a way that could not have been realized, or even imagined, 10 years ago. Just as important, the trilogy infused the fantasy genre with a grace and gravity unseen on such a huge scale. LOTR was an artistic and financial coup so impressive that even the Motion Picture Academy was bowled over, giving the film a record-tying 11 Oscars.Today the project sounds golden. But Hollywood didn't always think so. Disney-Miramax rejected Jackson's proposal, even at a compromised two-film length. The front-office pooh-bahs may have recalled the failure of Ralph Bakshi's 1978 animated version of The Lord of the Rings, also in two parts (the second half was never made). For less remote box-office evidence, potential sponsors had only to measure the $300 million Jackson needed to make the trilogy against the measly $35 million or so his five previous features had earned worldwide.

Those early films boasted a luxurious imagination and a talent for creating spooky or gory effects on minuscule budgets. Bad Taste, with the first-time director in a lead role, had aliens hunting down humans for their fast-food value—gourmet Guignol. Meet the Feebles was, we're pretty sure, the first all-puppet musical-comedy splatter film. The hero of Braindead (also known as Dead Alive) was sucked into the reproductive organs of his 20-ft.-tall zombie monster mom (a puppet), then fought his way out again. Only Heavenly Creatures, a rapturous, true-life study of teen obsession, generated a lot of critical heat outside the video-cult niche, but it still was no hit. What these films, along with the slightly pricier Frighteners, displayed was Jackson's gift for spinning far-out tales that, for all the blood on the walls, displayed a buff-savant's love of film's tricks and boundless possibilities.

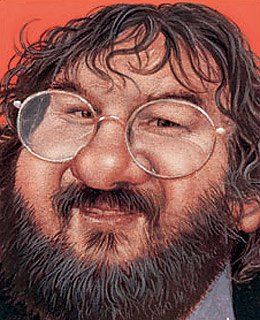

To be fair to the moguls who passed on LOTR, none of the early movies suggested that Tolkien and Jackson (whose own genial burliness suggests a cross between Sam Gamgee and Boromir) would be a natural match. Indeed, longtime Jackson admirers kept waiting for the Ring cycle to spin off into Dead Alive delirium. That didn't happen. The old films could be anarchic; the trilogy had to be conservative. Jackson's duty, as he saw it, was to make a faithful translation of Middle-earth—a kind of transmedial cloning. His triumph was to oversee a production as mammoth as his early films had been intimate, and to keep the grand scheme in mind while enriching each screen moment. Moviemakers appreciated the breadth and depth of his commitment. Moviegoers reacted in awe. And studio execs learned that once in a while it's a good bet to trust a director's passion and vision.

Now that Jackson has all this power, what will he do with it? Remake King Kong, a monster film he has loved since his youth. And Universal Pictures is happy to bankroll the third version of a story that most people thought was perfect the first time around (in 1933, when the big ape scaled the Empire State Building) and redundant the second time (in 1976, when Kong had a rendezvous with the World Trade Center).

This might seem to be the whim of a rich kid in a man's body. But the smart money was wrong before in underestimating Jackson's imagination and ambition. It would be folly to do so again.

From the Archives

Feeding on Fantasy: Forward into the past! At a time of uncertainty, American culture looks backward for comfort