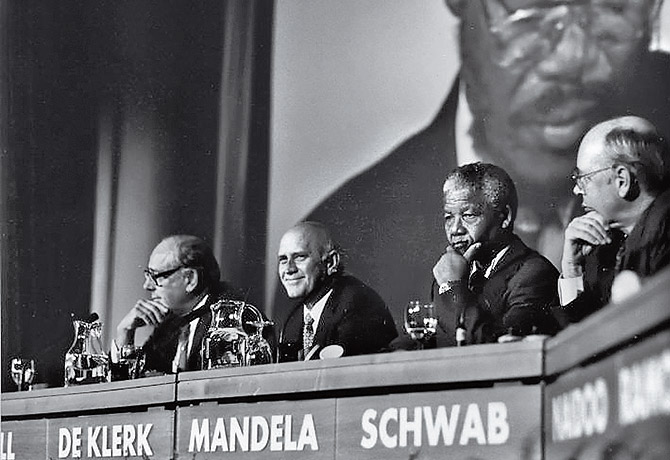

South African President F.W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela meet in Davos in 1992.

The alpine ski town of Davos has just entered its peak season. Every January, hordes of executives, world leaders, journalists and intellectuals descend on the Swiss village to ski and socialize as part of the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF). The five-day gathering is intended to provide a platform for debating pressing global challenges. This year's agenda will include international efforts to recover from the Great Recession.

For a ritzy confab that attracts everyone from Bono to Bill Clinton, the WEF got off to a humble start. In January 1971, Klaus Schwab, then a professor at the University of Geneva, chaired a meeting of European businessmen to discuss how their firms could compete with their U.S. counterparts. The group met in Davos, whose tuberculosis sanatoriums — now largely converted to hotels — were the setting of Thomas Mann's 1924 novel, The Magic Mountain. The meetings started off private and business-focused but expanded in scope and membership as political and social issues joined the agenda. In 1987 the group was rebranded as the World Economic Forum, and conflict resolution was added to its remit: it hosted a summit in 1988 that headed off war between Turkey and Greece and in 1992 the first sit-down between South African President F.W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela.

All the schmoozing and schussing have made Davos a popular target for antiglobalization activists. Police and protesters clashed in its snowy streets in the 1990s, while critic Samuel Huntington famously coined the pejorative term "Davos man" for what he saw as a whole species of aloof internationalist élites. For Mann's part, years after The Magic Mountain, he noted the peculiar effect Davos had on its sanatorium patients: The "narrowness of this charmed circle of isolation" created a "sort of substitute existence." Yet in Davos, he wrote, one reveled in "the hermetic, feverish atmosphere of the enchanted mountain."