A new inquiry ordered by Attorney General Eric Holder into the CIA's enhanced interrogation program may eventually reveal how far agency personnel strayed beyond the guidelines set by Bush Administration lawyers when questioning hardened terrorists. The furor over the program, which reached its height in the fearful months after September 2001, is fraught with moral ambiguity. But there's also a colder, more practical question: Did harsh methods like waterboarding cause terrorist suspects to give up valuable, actionable intelligence?

The program's defenders, led by former Vice President Dick Cheney, claim that so-called high-value detainees like 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed were initially resistant to interrogation but broke down under more coercive techniques — providing information that helped foil imminent terrorist plots and save thousands of lives. The proof, Cheney claimed, lay in two classified CIA memos that showed "the success of the effort."

Those memos were declassified on Aug. 24, along with a 2004 inspector general's report on the CIA's interrogation program. Rather than provide a smoking gun, the documents may have just created more smoke. The detainees who endured the harshest methods coughed up all sorts of information, including plans to attack U.S. targets at home and overseas. But the inspector general's report, which remains heavily redacted, notes investigators "did not uncover any evidence that these plots were imminent" and sidestepped the question of whether the information could have been gleaned by other, less brutal methods.

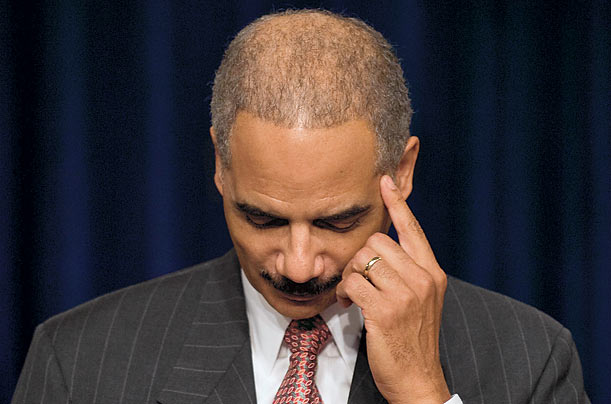

The recent probe ordered by Holder (above) won't be the end of the matter. It has already drawn fire from critics of Bush-era policies who say its scope is too narrow. Whether it is wise to prosecute those who carried out the questionable interrogations or to pursue those who authorized them is an issue of legality, morality ... and politics.