February 14, Qum, Iran

After Friday prayers on Feb. 24, 1989, about 2,000 Muslims gathered at Mastan Talao, a public square in South Mumbai. They had gone there to protest the British government's decision to protect Salman Rushdie against the fatwa issued 10 days earlier by Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini, Iran's Supreme Leader. Khomeini had condemned Rushdie's novel, The Satanic Verses, as blasphemous to Islam and exhorted his followers to carry out a death sentence. Rushdie, who lived in London at the time, was given 24-hour police protection, and another round of protests began. The crowd in Mumbai, who carried banners reading I AM READY TO KILL RUSHDIE and RUSHDIE — RUSH+DIE, were unaware that the march's organizers had been arrested the night before by Indian authorities or that the protest itself had been banned. Instructed to end the march, the police moved in and arrested most of the protesters, but a small group broke away and continued down the main road. Just before reaching Crawford Market — a grand 19th century fruit and flower market — a line of policemen stopped them. There was a confrontation, and within an hour the police had fired scores of bullets, killing 11 people including two pilgrims on their way to Saudi Arabia, struck as they watched from a balcony nearby.

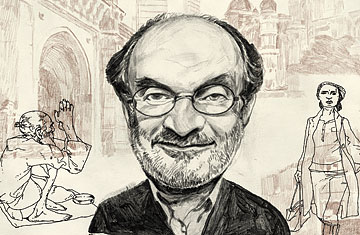

The furor over The Satanic Verses was one of those unsettling media experiences of the pre-Internet era in which images from distant corners of the globe seemed to coalesce into something bigger. A writer in London, rabid denunciations in Tehran, protests in South Africa and Pakistan, bookstores bombed in Berkeley. Mumbai (then called Bombay) was just one more angry city on the list. India lost more lives than any other country in the name of the fatwa, while the author himself survived almost a decade in hiding, publishing six books during his years undercover. The Satanic Verses is remembered 20 years later as part of a larger narrative about Iran vs. the West, but that is not the story Rushdie was trying to tell. The Satanic Verses was an attempt to engage in a conversation with India, and in particular with Mumbai, Rushdie's hometown, about whether its character as a multireligious yet secular society was strengthened or undermined by the expression of extreme, unpopular or unorthodox views. It is an argument that remains unresolved but is more urgent than ever.

Chaos Theory

Before the fatwa was ever uttered, Rushdie spelled out what The Satanic Verses was trying to say. In a letter to then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in October 1988, protesting his decision to ban the book, Rushdie wrote: "Let's remember that the book isn't actually about Islam, but about migration, metamorphosis, divided selves, love, death, London and Bombay." Jihadist groups were practically unknown at the time in India, but Hindu nationalist parties — the Shiv Sena in Mumbai (they were responsible for renaming the city) and its national ally, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) — were on the rise. Rushdie's response to their narrow view of a "Hindu India" was to write a book premised on the radical idea of an India broad enough to accommodate his florid, fantastical irreverence. Like Rushdie, his hero Saladin Chamcha (chamcha means flunky) was a Muslim only in the "lackadaisical, light manner of Bombayites." After years of living in London, Chamcha returns to Mumbai, electrified and confounded by what was once his home: "India; it jumbled things up."

Rushdie embraces that confusion. His India is a place where people are free to mix and match traditions, to satirize and discard them at will. As an Indian writer in London, Rushdie was the epitome of the cosmopolite — a world citizen — and that cosmopolitan vision comes to life in The Satanic Verses. The two protagonists, Chamcha and Gibreel Farishta (literally, Angel Gabriel), are both actors from Mumbai, one a British voice-over artist, the other a Bollywood superstar. They meet on a hijacked plane, magically survive its destruction and spend the rest of the novel circling back through their earlier lives. Both are psychologically damaged, and Farishta's delusions turn into the novel's controversial dream sequences, in which Rushdie reimagines the Prophet Muhammad's life. In the novel he is the Messenger, Mahound, in a place called Jahilia: "There is a god here called Allah (means simply, the god). Ask the Jahilians and they'll acknowledge that this fellow has some sort of overall authority, but he isn't very popular: an all-rounder in an age of specialist statues." The novel lurches back and forth between dream life and real life, and the two heroes eventually return to Mumbai.

The historical and religious allusions, Bollywood in-jokes and references to Indian politics made the book difficult reading, but they were essential to its vitality. E.M. Forster found something vaguely disturbing about the emerging cosmopolitanism of the early 20th century. "London was but a foretaste of this nomadic civilization which is altering human nature so profoundly, and throws upon personal relations a stress greater than they have ever borne before," he wrote in Howard's End. Rushdie revels in this strange new world. In the opening scene of The Satanic Verses, his heroes fall out of the sky and, thus completely unmoored, are reborn. "The Satanic Verses celebrates hybridity, impurity, intermingling, the transformation that comes of new and unexpected combinations of human beings, cultures, ideas, politics, movies, songs," Rushdie wrote in a 1990 essay. "It rejoices in mongrelization and fears the absolutism of the Pure."