December 13, Cape Town, South Africa

"SP observes that problems are there to be solved; life is fraught with problems. M. concurs and comments that however large problems become, there is always hope that they can be solved ... SP says he has emphasized ... the necessity for Africa to come to terms with the Afrikaner ... M. says he fully appreciates this and has come to know the Afrikaner better in prison."

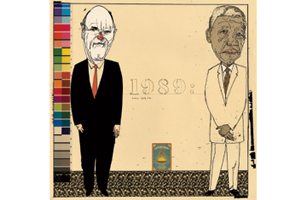

It is July 5, 1989. "SP" is South African President P.W. Botha and "M." is Nelson Mandela. These minutes, taken by Niel Barnard, the then head of South Africa's National Intelligence Service, record how, after 41 years of apartheid and 26 years in jail for Mandela, a white-supremacist President and a black revolutionary leader took the first steps toward peace. Mandela had been snuck through a back door into Botha's official residence in Cape Town, Tuynhuys ("Garden House" in Afrikaans). Botha poured the tea — a gesture of respect unthinkable under the white rule that prevailed. The discussion was short, just half an hour, and skirted the big issues. But after it, as Mandela records in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, "there was no turning back."

A little over five months later, Mandela was escorted from jail to Tuynhuys once again to meet Botha's successor, F.W. de Klerk. This time the discussion was more substantial. Mandela demanded De Klerk release him and his comrades, lift the ban on Mandela's party, the African National Congress (ANC), and end the state of emergency. De Klerk made no promises, but did not argue either. "From the first I noticed that Mr. De Klerk listened to what I had to say," wrote Mandela. "Mr. De Klerk ... was a man we could do business with." Crucially, De Klerk's reaction matched Mandela's. "The first time I met Mandela ... I noticed how good a listener he was," De Klerk tells TIME. "I reported back to my constituency and said: 'This is a man I can do business with.'" Less than two months later, De Klerk, whose previous reputation as a hard-liner belied an equally hard-nosed practicality, lifted the ban on the ANC. On Feb. 11 Mandela, by then 71, walked out of prison with a simple message. De Klerk was a "man of integrity," he told a crowd of thousands in Cape Town. A settlement was possible.

What followed would often be less than a fairy tale. During the negotiations to end apartheid, Mandela accused De Klerk of resisting majority rule and "waging a covert war" against the ANC, with the Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) as its proxy. "Our relationship was up and down," admits De Klerk today. But the way was set. The Tuynhuys meetings had laid the foundations for a new country. "After that, the end of apartheid became inevitable," says Allister Sparks, whose book Tomorrow Is Another Country documented the transition. The path to the first free elections was marred by violence and killings — there were attacks by whites on blacks, by blacks on whites, and thousands died in township battles between the ANC and the IFP. But because the change had begun in cordial discussion, it did not, as many feared, lead to civil war. "Even when it was testy, we always found it possible to raise the issue above the tension so that the process could move forward," says De Klerk. Black did not eject white in a violent overthrow. Whites did not circle the wagons and fight to the last man. Instead, in 1994 South Africa held an election, and Mandela won.

The Tuynhuys effect resonated way beyond South Africa. Africa was reunited with its greatest leader and the world gained a man who quickly became a kind of universal conscience. It also set a global precedent. The end of apartheid was not, as many took it at the time, primarily a story of improving race relations with parallels in American desegregation — though healing the race divide was certainly an objective. Rather, as Sparks says, it was first and foremost about confronting a conundrum all too common around the world: how to bind together two nations in one state. "It's like Israelis and Palestinians," says Sparks. "Or Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland." The miracle of South Africa is that the attempt more or less succeeded.

Despite many setbacks and a persistent racial distrust, a new multicolored South Africa — a Rainbow Nation, in Archbishop Desmond Tutu's phrase, where color is no longer a legal distinction, and a diminishing social and cultural one — is an emerging reality. Middle-class black South Africans now number in their millions. Johannesburg, the business capital, is home to a new black élite. Afrikaners, courted assiduously first by Mandela and now again by new President Jacob Zuma, are finding a place under this new banner. "Afrikaners have been in Africa as long as whites in America," says Sparks. "In giving up their country, the big question was what would still define them as a people?" The answer was culture. Afrikaners discovered their identity did not derive primarily from political power. That is gone today, but Afrikaner arts — from literature and art to cookery and rock festivals — is in renaissance. "And its theme is: we are South Africans," says Sparks.

Questions of identity and nationhood are some of the most fundamental in politics. For South Africa's rulers, old and new, they were defining everything else. As he later admitted, Mandela did not spot the danger of HIV/AIDS until it was well on its way to killing 2.8 million people and infecting 5.7 million in South Africa alone. The ANC saw reports of South Africa's violent crime in racial terms, as a Western attempt to denigrate Africans. Mandela's successor Thabo Mbeki even regarded AIDS as a Western drug-company conspiracy. Under the ANC millions of South Africans have been connected to electricity and water and given real homes. But, shamefully, inequality and the number living in poverty has actually grown. In the end, South Africa's great triumph was also a great distraction. Twenty years later, the Tuynhuys meetings still resonate — not least in the minds of their participants — but millions of South Africans find their more immediate concerns go unnoticed in the shadow of this towering history.

For a country facing such daunting challenges, perhaps the greatest legacy of Tuynhuys is the spirit in which the meetings were convened. As Mandela said: "However large problems become, there is always hope that they can be solved." Botha had poured the tea. And the principle that simple act established — pragmatism for the sake of peace — has endured. On April 14, 1994, four years after they first met and 13 days before South Africa's first free general election, De Klerk and Mandela, by then joint Nobel Peace Prize winners and rival party leaders, held a televised debate. De Klerk criticized the ANC's spending plans. Mandela accused De Klerk of fanning race hatred and opposing redistribution to blacks. "But as the debate was nearing an end, I felt I had been too harsh," Mandela wrote in Long Walk to Freedom. "In summation, I said, 'The exchanges between Mr. De Klerk and me should not obscure one important fact. I think we are a shining example to the entire world of people drawn from different racial groups who have a common loyalty, a common love, to their common country ... We are going to face the problem of this country together.' At which point I reached over to take his hand ..." South Africa's miracle, the story of how in two short meetings the most bitter of enemies learned to drop their fists and try a handshake instead, still illuminates the world with hope.