As he lay dying in a Princeton hospital bed in 1955, Albert Einstein continued until his last hours to scribble equations in pursuit of his elusive goal of a unified field theory tying together all the forces of nature. At the time, that task was being made more complex, but perhaps eventually more achievable, by a Japanese physicist whom he had recently met. Yoichiro Nambu had arrived at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in 1952, having survived service in the Imperial Army. After spending time with Einstein, he moved on to the University of Chicago. There he began studying superconductivity, a phenomenon in which a material offers no resistance to an electrical current, and discovered that it could be explained using a concept called "spontaneous symmetry breaking."

Scientists have always sought symmetry in nature, meaning laws that are the same in all circumstances. Nambu realized that when a situation occurs that defies symmetry, a new particle is born. This led to the discovery of a bestiary of particles. A major task of the Large Hadron Collider, the particle accelerator near Geneva that was turned on last year, will be to search for a particle known as the Higgs boson that, according to Nambu's theory, is responsible for breaking the symmetry between electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force.

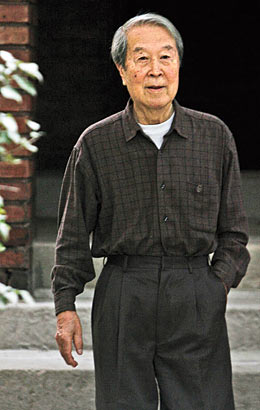

But can Nambu, 88, help Einstein's ghost join together what God has rent asunder? Perhaps. His theory holds that quarks behave as if connected by strings, which serves as a foundation for the string theory that some physicists hope could fulfill Einstein's quest. So for "the discovery of the mechanism of spontaneous broken symmetry in subatomic physics," Nambu shared the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physics — and wins selection to the TIME 100.

Isaacson, a former managing editor of TIME, is the author of Einstein: His Life and Universe