(2 of 4)

An equal chance. Lincoln's thoughts on money are relevant today because he reminds us of the best aspects of the American economy — not just how to survive a crash but why it matters that we do. The boggling complexity of today's marketplace would amaze him, but the fact that bust has once again followed boom would not. Lincoln lived through two major economic crashes, in 1837 and 1857, and he learned some timeless lessons. He foresaw, in the Union he struggled to preserve, an open, competitive, capitalist, enterprising nation, tied together by rapid transportation and communication. He believed that government had a leading role to play in building the infrastructure of a growing economy. But the guiding principle for all of it, the whole reason for the nation's being, was that "equal chance" — the humble citizen's right to get ahead. Lincoln understood that economic freedom was the bedrock of political liberty. One is not possible without the other. Thus it was not just virtuous but also necessary to fight the slave economy. Lincoln has been criticized for saying, during his famous debates with Stephen Douglas, that white and black might never be equal in social terms. But he was firm on the economic question: "In the right to eat the bread, without leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns," Lincoln insisted, a black person "is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man." Another time, responding to the Southern argument that Northern factory workers were, in essence, just as enslaved as plantation hands, Lincoln zeroed in on the crucial difference. "There is no permanent class of hired laborers amongst us," he said. "Free labor has the inspiration of hope; pure slavery has no hope." (See pictures of the civil rights movement, from Emmett Till to Barack Obama.)

There is little trace of this money-conscious Lincoln at the great memorial on the National Mall. To catch the scent of that man — the one who knows what we're going through and why the right solutions remain urgently important to the world — we're better off visiting another white-stone, Greek-style temple. Older and odder than the monument on the mall, this Lincoln memorial is situated on an out-of-the-way hilltop in western Kentucky, roughly on the spot where Lincoln was born.

Humble Beginnings

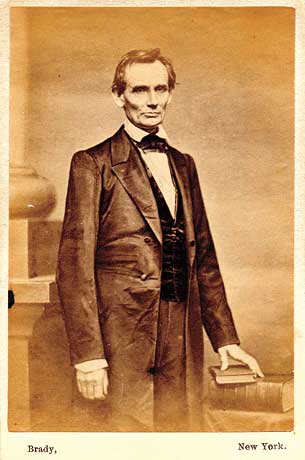

The cornerstone of the Kentucky temple was laid a century ago, 13 years before the dedication of the memorial in Washington. But instead of a statue inside or tablets carved with Lincoln's words, the birthplace monument contains a crude one-room hut with a mud-and-stick chimney — a replica of the mythic log cabin. Putting a dirt-floor hovel inside a columned temple is a bit weird, yes. On the one hand, it is a way of sanctifying the Lincolnian ideal of upward mobility. On the other hand, the transfiguration from squalor to shrine sanitizes Lincoln's life story and in this way makes it harder for us to understand the intensity of his ideas about money. Lincoln knew the dead-end life of an undeveloped economy: poor, nasty, brutish and short. The romance of the log cabin masks a grim reality. (See pictures of Lincoln.)

When Lincoln was born here on Sunday, Feb. 12, 1809, he entered a world as harsh and primitive as if he had been born a thousand years earlier. The simple act of giving birth put his mother in mortal danger, and her only protection was the old "granny woman" summoned from miles away. Her baby was washed in water carried uphill from a dripping spring, then wrapped in animal skin against the winter cold and put in a bed of corn husks standing on a damp earth floor beside a smoky fire.

In later years, Lincoln allowed his supporters to portray him as a sort of backwoods superman, for already the young nation was beginning to glamorize its frontier roots. Even in the heat of the "rail splitter" campaign of 1860, however, he resisted the idea that life in the wilderness was grand and pure. All the hardship and sorrow of what he called "stinted living" could be condensed, Lincoln said, into a single line from the poet Thomas Gray: "the short and simple annals of the poor." His strongest boyhood memories were of death and near death: the time he almost drowned, the time he was brained by the kick of a horse, the early deaths of his younger brother and beloved mother and eventually his sister Sarah.

Another monument, this one at Lincoln's boyhood home in south-central Indiana, comes a bit closer to the dark reality — especially if you approach the place in winter, as the Lincoln family did when Abe was 7 years old. A sharp wind drives scattered snowflakes, and as you walk deeper into the woods, you might try to imagine the first months, before the tiny cabin was built, when the little family huddled for shelter under a flimsy three-sided windbreak.

Here sits another replica of the iconic cabin, this time in its proper physical context. Carl Sandburg calculated that the walk for water was a mile each way, but try as you might to put yourself in the place of a barefoot child making that long trip with that heavy bucket to that dark and drafty little room, it's almost impossible. For you know that if you grow cold or bored or turn an ankle or run a fever, you'll soon be back in the modern world, temperature-controlled and professionally doctored. Within two years of his family's trek into Indiana, Lincoln's mother was dead. The boy watched her suffer and probably helped make her coffin. His father Thomas Lincoln, unable to cope with farm and family by himself, returned to Kentucky, leaving his children nearly abandoned in the hardwood forest. Abe was 10, Sarah 12; a teenage cousin was their only company. "The panther's scream filled night with fear," Lincoln later wrote. When Thomas finally returned months later with his new wife, they found the future President and his sister living almost like animals, filthy and deprived.