Dubai is a stunning example of rapid, efficient, planned urban development — but is it a real city? It is spectacular, but is it anything more than mere spectacle? These are the hard but compelling questions we must ask as we watch the meteoric expansion of Dubai, Doha, Abu Dhabi and other Gulf cities. What, in short, do they represent, and what may they portend?

I am a fan of Dubai and all that it has achieved. This is why I seek signs that it has crossed the threshold from a manager of successful construction projects to a contributor to civilization. If the Gulf's emerging hypercities are to have lasting meaning, they will need to build on their impressive physical infrastructure an edifice that is much more solid and durable: an architecture of the human spirit. I am rooting for these cities to grow in the realm of ingenuity — to create wealth in art, science, poetry, music, literature, journalism, research and education.

A few recent developments suggest that some in the Gulf have started to explore this terrain. Governments are already making massive investments — tens of billions of dollars — in knowledge- and culture-based ventures, including a spin-off of the Louvre in Abu Dhabi, the Dubai School of Government, Qatar's Arab Democracy Foundation and offshoots of foreign universities like Georgetown and Cornell. Other Arabs have attempted to go down this road before, but their journeys were cut short by the modern Arab security state's inability to allow the free flow of ideas. In many countries, artists are still severely curtailed, journalists and writers handcuffed by security agencies, universities stultified by a culture of autocracy and mediocrity.

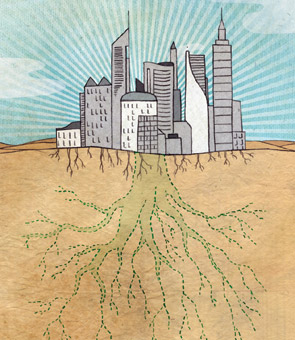

Now the Arab world has another chance to fulfil its potential. In homes, offices and cafés around the Middle East, we talk about "the Dubai model." As it is presently defined, this means fast growth, bold expansion, streamlined service delivery and openness to the rest of the world. These are remarkable achievements, but they are not the key attributes of great cities. Arabs have a new opportunity to create urban powerhouses that are incubators of talent and generators of ideas, admired for their dynamic, productive citizens, award-winning authors and patent-wielding scientists. That is the model Dubai should aspire to become.

Progress will be neither quick nor easy. The Gulf's hypercities currently have three of the six elements that splendid, enduring cities such as London, Istanbul, New Delhi and New York City share to varying degrees: multinational populations, expanding economies and efficient infrastructure. The missing elements are cultural production, intellectual and scientific output, and pluralistic politics. Political life will take time to develop in the small monarchies and emirates of the Gulf. In the meantime, how well they tap the creativity and brainpower of their citizenry will determine whether Arab Gulf urbanism can enrich the spirit.

It is fascinating to note that, since 1980, Dubai has followed the same path that transformed Beirut from a small town into a globalized city between the 1860s and the 1960s. Both cities spurred their growth by offering the surrounding region entrepôt and trade facilities, quality professional services in areas such as engineering and advertising, a major international airport, excellent educational facilities and rich job opportunities. They both became centers of tourism, lavish consumerism and serious banking, along with occasional smuggling and money laundering.

But as Beirut enjoyed economic prosperity, it also poured investment into the arts, research and innovation. Today, the city still boasts the Arab world's best universities, most vibrant cultural scene and liveliest media, despite repeated wars and bloodshed, tension with Israel and a mediocre political class. Why? Because societies that create artistic and intellectual wealth in their cities also create the storehouses of knowledge, identity and self-confidence that allow them to survive and rejuvenate after periods of conflict or destruction. Their cultural assets are deep and indomitable, their reserves of civilizational protein substantial.

The dizzily growing cities of the Gulf have yet to achieve the institutional critical mass that would allow them to produce or export lasting ideas. They still mostly erect awe-inspiring buildings. We should acknowledge these structures as an important first step, admirably imagined, planned and implemented. However, these cities should now reach for the next phase of their urbanism, one that matters and endures, rather than merely dazzles.

Rami Khouri is director of the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the American University of Beirut