Few people doubt that embryonic stem cells may offer extraordinary opportunities to treat or prevent disease, but few deny either that the politics surrounding the idea has often seemed as complex as the science. All that may have changed last year with the announcement that it was possible to give adult human cells many of the characteristics of embryonic stem cells, avoiding entirely the issue of whether embryos would be destroyed in the process. The new cells, known as induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, are expected to live for a very long time while retaining the ability to form all of the different tissues found in a human body.

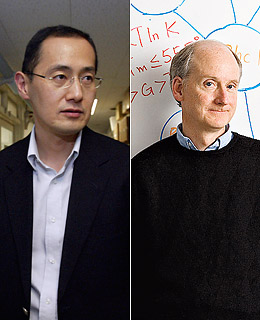

Shinya Yamanaka, 45, working in Japan's Kyoto University with mouse cells, made the iPS breakthrough. He screened 24 candidate proteins before finding four that were able to reprogram adult cells, reverting them to their embryonic state. He and others then showed that these factors are also effective in human cells. Developmental biologist James Thomson, 49, of the University of Wisconsin was the first to identify a slightly different group of factors that do the same.

One day iPS cells may be used to replace cells damaged or lost in disease, but much remains to be learned before such therapy would be appropriate. As a step along the way, iPS cells from patients with an inherited disease will offer opportunities to study illnesses such as als and Parkinson's and psychological ailments, as scientists program the cells back to their embryonic state and watch them mature in the lab. In the process, they may pinpoint the breakdowns that lead to the disease. The precise mechanism that led to Yamanaka's and Thomson's achievement last year is not yet understood, but the potential of that achievement is; it is a potential that could be unlimited.

Wilmut cloned the first mammal—a sheep he named Dolly—using stem cells