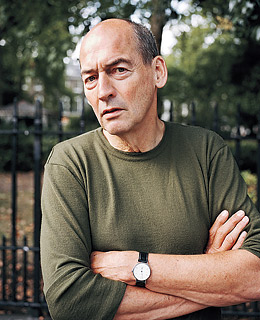

We tend to think of great architects as people who impose their vision on the world. They come bearing significant forms and whip cities into shape. Rem Koolhaas is different. The Dutch-born architect-polemicist doesn't think architecture should change the world so much as the world should change architecture. In cities from Lagos to Lahore, he has looked at the messy facts on the ground to see how designers and planners can submit themselves most usefully to the realities all around them. He has led graduate seminars on the "generic cities" of the developing world, not to see how those places can be rationalized but to learn from their irrationality. In Delirious New York, his 1978 history-as-manifesto, he even spoke up for congestion, for urban density and the creative contagions it generates.

Despite this philosophy, Koolhaas, 63, is not one of those architects much concerned with producing buildings that defer visually to their surroundings. With his partners in the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), the firm he co-founded in 1975 in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, he has produced some of the most distinctive buildings of the past 20 years. When Seattle asked for a new public library, OMA delivered the last word in rare volumes—an irregular stack of cantilevered spaces wrapped in angular glass walls and a honeycomb of steel. And his new Beijing headquarters for CCTV, China's state-controlled television network, is a prodigious twist on the idea of an office tower, a kind of backflip in glass and steel. He may not be a man who wants to impose his vision on the world, but somehow the world is looking more and more like he wants it to.