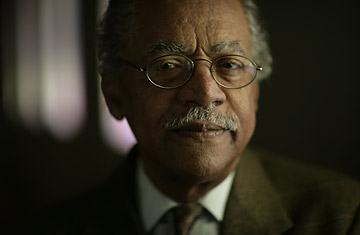

Rev. Samuel "Billy" Kyles had bought a new Memphis home in 1968 and was honored that Dr. Martin Luther King planned to come over for dinner while he was in town backing up striking garbage workers.

King jokingly warned Kyles not to treat him like another preacher in Atlanta who had invited him to dinner at his house. When he and his wife Coretta arrived, the house had no furniture and their dinner was served cold on a card table.

"If I go to your house and I discover that you bought a house and can't buy food," King told him. "I'm gonna call all the TV and radio stations and tell them 'Kyles bought a house, but he can't buy food.'"

King and his aides from the SCLC made plans to eat at Kyles' home on the evening of April 4. Kyles arrived at the Lorraine Motel to pick up his friends at 5 p.m. and came to King's room, where he also met up with Rev. Ralph Abernathy.

"The world has asked: what did three preachers do in a room for an hour," Kyles said. "It was really three guys hanging out."

He described the conversation as lighthearted. King did some remembering of his father, Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., and his maternal grandfather, the powerful minister A.D. Williams. In fact, the mood was a complete switch from 24 hours before when King had been talking about death.

But an electric, if not prophetic, speech at Mason Temple the night before changed his outlook. "It was as if he had preached himself through the fear of death...and the next day he was in a lighthearted mood. He was almost giddy," says Kyles.

After the three men finished talking, Abernathy went into the bathroom to shave and Kyles left the room for his car, beckoning everyone to hurry up.

King exchanged a brief joke with Jesse Jackson, who wanted to introduce bandleader Ben Branch to King. King liked Branch's rendition of Precious Lord.

"And Martin was leaning over the balcony, not trying to shake hands, but leaning over talking to Jesse and Ben Branch. I stepped away, I started down the stairs. I said 'Guys, come on. We have a rally tonight, let's go.' I got about five or six steps and the shot rang out."

"KA-PAOOOW."

Everyone's first instinct was to duck for cover, not knowing if the shooting would continue. It didn't. When Kyles went over to King, he was sprawled on the floor with a mortal wound. A halo of blood circled his head.

Kyles tried to call the motel operator so that she could summon an ambulance, but she had come out into the yard beneath the balcony where King lay. When the woman, who was the motel owner's wife, saw his body, she suffered a fatal heart attack.

"I thought I was having a nightmare, but I was awake. 40 years ago, I had no words to express my feelings. 40 years later, I still have no words to express how I felt," Kyles said in a near-whisper.

Four decades later, Kyles remains in Memphis, building his ministry, Monumental Baptist Church. He also frequently speaks on his experiences with King, and gives tours at the Lorraine Motel, now refurbished into the National Civil Rights Museum.

Kyles remembers a visit from Nelson Mandela, who told him that when the South African movement was feeling so low, they'd think about Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement in America and they'd would be renewed to continue their journey.

"And with all that (Nelson) Mandela had been through in his own life — 27 years in jail, losing all of his rights — he openly wept," said Kyles.

Kyles sees the civil rights movement as ultimately triumphant. He remembers the stark segregation of pre-King Memphis and the integrated society he sees now. But the work isn't done, he says.

"I don't think there will be a time when we can say, 'Now King's dream has been realized, we can go on to the beach and have fun.' The dream evolved, it's not just for black people, it's universal. People everywhere can dream and want to dream about freedom and equality and they use Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement as a model all over the world."