For years, the country's economic situation had seemed hopeless. Abundantly endowed with minerals and oil and gas deposits, it has nonetheless swung from booms to busts and back again. Its politics are hopelessly corrupt. The central government, far from being an effective regulator, serves mostly as a handmaiden to a powerful group of oligarchs, making it that much easier for the rich to get richer. And as the oil and mineral barons party on, the rest of the country suffers ...

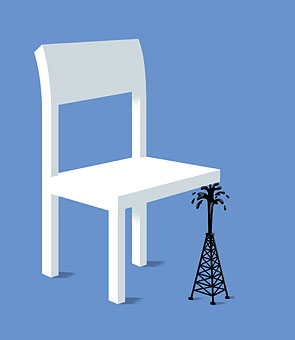

It's called the "resource curse" — and what it means is that many economists have come to accept that for developing countries, less is more. Think of Ghana and Zambia, which upon independence expected that their cocoa plantations and copper deposits would ease their way to prosperity — and were quickly disabused of the idea. Think of Saudi Arabia, where they import Filipinos and Palestinians to do the work as the sheiks jet off to party and shop in London and Paris. When the Netherlands in the 1950s and '60s discovered a huge amount of natural gas off its shores, only to see the rest of its economy subsequently go into the tank, the phenomenon became known as the "Dutch disease."

It's coming to the end of its shelf life. The historic commodities boom that we are living through now shows that the Dutch disease is just as often absent from resource-rich countries as it is present. The key is governance. Yes, commodities can indeed produce rent-seeking, and can bump up the external value of a currency, making it hard to produce other goods for export. But well-governed nations find ways to insulate their economies from the downside of commodities. Some of it, as Norway has shown, is just straightforward economic fundamentals: sound monetary policy, open trading and investment regimes. Enforced laws against corruption are basic. So, too, is using natural endowments to make key industries more efficient and productive, in part by utilizing (and indeed, prodding) innovations elsewhere in the economy. Australia, points out Stanford economist Gavin Wright, receives more income from intellectual property associated with the mining industry than it does from wine exports.

Skeptics of the Dutch disease's demise point to Russia as the most prominent example of a hugely endowed country making bad choices. A chaotic democracy has become an authoritarian, one-party state guided by former Gazprom chairman Dmitri Medvedev, who is often regarded as little more than a front man for former President Vladimir Putin. The crippling corruption of the 1990s, in conventional wisdom, is now simply benefiting a different cast of characters.

Maybe so. But nothing guarantees that doleful outlook — surely not the geological gift of massive resources. History, if it shows anything, shows that resource-dependent, boom-and-bust, poorly regulated countries can — and do — change. Consider the country described in the first paragraph of this story. It is, true enough, Russia today. But it's also a fair description of another country, at the start of the 20th century. The United States has come a long way since then.