Facets

Available Dec. 25, List Price $39.95

If there were four great silent film comics — granted, a big if — they were Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and Langdon. The first three have been fully celebrated in movie revivals, DVD collections and, from the film historian Kevin Brownlow, exquisite documentaries. Langdon was as famous and acclaimed as the others, for a couple of years, but today his work is undersung and virtually unseen. His three best features — Tramp, Tramp, Tramp; The Strong Man; and Long Pants, all released within about a year in 1926-27 — can be found on a Kino DVD, but the short films for Mack Sennett that established Langdon's style were hard to find.

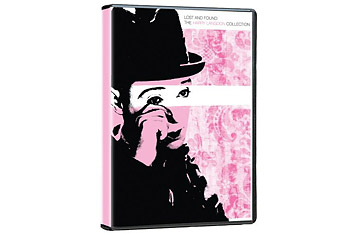

Now the devoted FOOFs (friends of old films) at All Day Entertainment have produced a four-disc extravaganza that means to retrieve Langdon from the cobwebbed attic of film history — literally, since many of the items preserved here had to be stitched together and spiffed up from moldering nitrate and scratchy 16 mm prints. Lost and Found collects 17 of Langdon's silent shorts plus scraps of others and what's left of his feature debut, His First Flame. You also get a feature-length documentary, produced by David Kalat, that's filled with the acute assertions of Langdon scholars. Kalat couldn't get the rights to the Kino movies, so a crucial chunk of the Langdon legacy is missing, but the doc makes an airtight case for the comic's importance, and demonstrates the devotion of movie scholars that rescued and restored his movies.

To TIME film critic James Agee, in his Life essay "Comedy's Golden Era," Langdon "looked like an elderly baby and, at times, a baby dope fiend; he could do more with less than any other comedian." That sentence captures the two essential traits of Langdon comedy: his infantilism and his passivity. He had a round, chalk-white face and an infant's pot belly. His shape will remind older viewers of Baby Huey, or of Droopy, the hangdog hound of Tex Avery's MGM cartoons — except that Droopy always gets his man (wolf), and Harry usually gets had.

That's because his character has no will power, or, for that matter, won't power. He seems like a spectator in his own movies; he is often the plot's collateral damage, swept along and away by the accidents of narrative, by the urges of other characters, by sheer dumb or rotten luck. In a typical Langdon gag construction, there will first be some action (a car whizzing by, a falling object), then we wait for Harry's reaction, then wait some more, and then he makes a little jump. His nervous system is so sluggish, he seems in a dream, a stupor or a coma. He makes Keaton, famous for his stone-faced stoicism, seem like Jim (Mad Money) Cramer by comparison. This sly torpor gives his movies, made more than 80 years ago, a very modern, almost drugged tone. Looking at Langdon can be like staring at a clock with no second hand.

Chaplin had come to movies at 24, Keaton at 21, Lloyd at 19. Langdon was 40, with a lifetime playing in circuses and doing a vaudeville act about a couple's troublesome new car, when he joined Sennett. There were familiar elements to his appearance: his walk is a Chaplin-like waddle; as Agee noticed, "his vest buttoned at the wishbone," in the Chaplin style. He certainly borrowed from routines of the Big Three and built on their notion of the little guy, the nebbish hero, the tramp who becomes the champ. But any close similarity to Chaplin, Keaton and Lloyd ended there. Their screen characters, however buffeted by circumstance, eventually seized their destinies. The happy ending in Langdon films, if there was to be one, came because somebody else took pity on him or fell in love with him. His passivity remained pure; his fate was up to his screenwriters.

Sennett, who had discovered Chaplin, was known for his films' frenetic slapstick: the Keystone Kops rushing helter-skelter after the Mack Sennett Bathing Beauties. So it's a mild astonishment that he let Langdon do his nothing-doing thing. In the early shorts Sennett surrounded him with meta-movie gags: speeding up or slowing down the film, inserting word balloons over his head. Gradually, though, the Langdon team — director Harry Edwards and writers Arthur Ripley and Frank Capra — jettisoned the trick shots and concentrated on constructing storylines into which Langdon could wander and become amusingly enmeshed.

His films used some routines Langdon had perfected in vaudeville, like his "leaning act." In His First Flame, he gets conked on head and slowly tilts about 30 degrees to his right; he holds for a beat, then tilts to his left and finally, gracefully falls over — a classic stunt. Langdon's writers extended some bits to near-infinity: in Soldier Man the lighted fuse to a bomb takes an agonizing 6 mins. 26 secs. to explode. And they were not above repeating gags; they found endless merriment in the notion of his mistaking a prosthetic leg for a real one, and often put Harry in women's clothes, or had him talk to store dummies. The climax to His First Flame has him rushing into a burning building and carrying a female mannequin down a steep ladder, only belatedly noticing she's not real. She could be his soul mate, since in his films Harry often seemed less a human being than a marvelous prop.

As flummoxed as Harry was by most things he encountered, he was especially baffled by women. They come in three stereotypes: the harridan wife, the conniving vamp and the dewy-eyed girleen. All make him uneasy. He'll hold a woman's hand for a second, then drop it as if it's hot. In His First Flamehe's at an all-girls' school giving a graduation speech: "Women and — Why." When the women in the audience vigorously applaud, he backs up, startled; even their approval frightens him.

In one of Langdon's best films, the three-reeler Saturday Afternoon, Harry is married (to a shrew) but, when a friend invites him on a double date, Harry goes along — not because he's a lecher but because he lacks all sales resistance; it's as if he's been hypnotized and will dumbly follow any command. When the other couple, on either side of him, chat away, Harry observes with intensity and not a little fear; he watches in embarrassment as they kiss, then rubs off the invisible stain of the smooch as if he were the recipient and his wife could see them. He's like an alien sent to earth, consistently baffled by the inhabitants' strange customs. And his reactions are no more gallant, or human, to women than to men. When a woman slaps him, he tosses a brick at her.

Soldier Man casts him in a double role: as the drunken king of Bomania and his lookalike, an American G.I. stranded in Europe and unaware that the war has ended. After nearly a year foraging for food, the G.I. is starving. This appetite overcomes all others, including sex. The Bomanian queen, thinking Harry's her husband, wants to get close enough to kiss him and kill him. She caresses him with one hand, holding a dagger behind him with the other. But Harry is so obsessed with eating that he takes forever to plant one on her. When he does, the innocent impact is so strong that she drops the dagger and crumples in dazed ardor to the floor. Harry's response to this display of royal passion? He gets more food.

Langdon's movie career was a shooting star that skyrocketed and vanished within two years. He fired Capra, who had directed The Strong Man and Long Pants, and directed himself in a few more silent features. His eminence was over, but he got supporting roles in talkies, where his quavery tenor voice sounds remarkably like that of Lou Costello, who would become a comedy star with Bud Abbott in the 40s. He also worked with Stan Laurel, whose clueless character owed a lot to Harry's. Langdon died in 1944, unable to survive long enough to be cheered by Agee's praise, or Walter Kerr's in his book The Silent Clowns. But the real heroes of the Harry Langdon saga are the FOOFs who cherished and saved his best old films. Their love for him is evident in every restored frame of this invaluable collection.