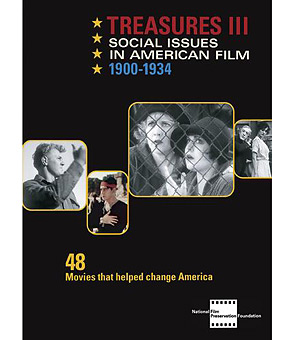

Treasures III: Social Issues in American Film, 1900-1934

National Film Preservation Foundation

Image Entertainment

Available Oct. 16

This third collection of rare artifacts from major U.S. film archives holds a rear-view mirror to American society as reflected in early fiction and documentary films. In 48 short and feature-length works spanning more than 12 hours, we see issues of the day — immigration, women's and workers' rights, questions of religion, abortion, war and peace — through the new medium that for many audiences was their main source of news, in a time before radio, television and the Internet. (Each film in this four-disc set has a musical score and a helpful narration by one of 20 scholars. There's also a 192-page book of program notes assembled by the project's curator, Scott Simmon.)

The package includes some famous Hollywood silent films: Cecil B. De Mille's The Godless Girl, a fantasia on atheists in high schools; William Desmond Taylor's visually rapturous The Soul of Youth, on the raising of orphans; Lois Weber's birth-control screed Where Are My Children?; and the Richard Dix Redskin, a Technicolor epic preaching tolerance and ethnic identity ("Go with the white man," a chief tells his son, "But come back to me — an Indian"). Yet the true unearthed treasures of this invaluable set are the newsreels, cartoons and fiction films from the dawn of movies. Some are more than a century old, and haven't been seen publicly since they first appeared in nickelodeons.

A 1901 political satire, Kansas Saloon Smashers, shows a Carrie Nation-type temperance terrorist wielding her axe in a saloon. The 1906 The Black Hand, one of the first Mafia movies, shows good Italians (a butcher and his plucky daughter) battling bad ones (hard-drinking, card-playing, child-abducting gangsters). An episode of the 1915 serial The Hazards of Helen shows the heroine (and co-director) Helen Holmes as a railroad telegrapher who thwarts the bad guys by walking a thin high board, swinging from a bridge onto a moving train and other Jackie Chan stunts. In the 1918 cartoon Uncle Sam Donates for Liberty Loans, the symbol of America first contributes his savings, then strips off and gives away his shirt cuffs, collar, coat, vest, shirtfront and hat — all to support the boys who'd gone to fight in the Great War. The moral, applicable today: "Pay Our Debts and Bring Back Our Boys!"

Today's old folks may astonish their grandkids when they tell them that a U.S. war once required sacrifice from civilians as well as soldiers. Another 1918 war-bond movie, 100% American, stars Mary Pickford, the silent screen's reigning actress, as Mayme, a young woman who learns that "self denial at home will assure victory abroad." While her selfish friend Tillie is pegged as "a slacker," Mayme swears off luxuries (a 25-cent sundae at the soda fountain) to invest in Liberty Bonds for the war effort. For those who ever wondered about Pickford's appeal, the film is a demonstration of the star's pert adorability. It's also a charming early example of patriotic propaganda. 100% American ends, Hollywood-style, with Mayme's good deeds rewarded: her soldier beau returns home intact.

The rehabilitation of wounded war veterans is a subject treated in small but potent group of documentaries (including John Huston's Let There Be Light from WWII and Patricia Foulkrod's The Ground Truth from the Iraq occupation) and fiction films (think of Marlon Brando in The Men, Jon Voight in Coming Home). The Reawakening, a 10min. documentary made within months of WWI's armistice, may have been the first film to show American audiences the disasters of war, and the hope for healing. We see one-legged men on crutches (some of the 204,0000 soldiers wounded in the conflict) enter a military hospital to receive physical, emotional and occupational therapy. Phantom limbs are fitted with prostheses; vets get individual attention in a group setting; they are encouraged to exercise their muscles and their minds, given writing and typing tasks, taught such skills as woodworking, painting, radio assembly, jewelry crafting, car repair.

This understatedly inspiring document was produced by the Ford Motor Co., a pioneer in short films on political and social subjects. Another Ford-sponsored movie included here is The United Snakes of America, a 1917 editorial cartoon in animated form. It shows the forces of good — Uncle Sam, a soldier and a sailor — nearly strangled by such enemies of the war effort as "Pro-German press," "Congressman," "Senator," "Strike" ... and "Clergeman" (clergyman), thus linking pacifist preachers with those accused of subverting the war effort.

Many industrial and government organizations recognized the power of film and sought to harness it. One was the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which produced films that, in 1923 alone, were seen by 4.5 million Americans in schools, churches and grange halls. Many films had utilitarian titles: The How and Why of Spuds, and Cranberries and Why They Are Sometimes Bitter. But one, the 1926 Poor Mrs. Jones!, goes beyond its propaganda message — why farm life is worth sticking with in an age of urban resettlement — to paint a subtle portrait of restless womanhood.

Directed by Raymond Evans, head of the USDA's Office of Motion Pictures, Poor Mrs. Jones! depicts a Maryland farm wife, Jane Jones (Leona Roberts), who flings an angry ultimatum at her husband: change my life or let me leave! Instead of getting mad, he consoles her — a closeup of his suntanned hand on her white one indicates his care for her — and suggests she visit her sister in Washington, D.C.

Sis, her husband and young son are cheerful about their walkup apartment, but a closer glance shows that the man's short cuffs are frayed, and at night Junior sleeps in a makeshift bed, Dad on the fire escape (to make room for the visitor). To Jane, the city is all chaos and threat: a jumble of shuffling legs outside a movie theater, the hysteria of shoppers at a clothing sale. But the movie editorializes only in whispers. The sister is sweet-souled, rubbing Arnica on Jane's tired feet, while Jane is sharp-featured, easily harried and no beauty; she looks like Margaret Hamilton photographed by Dorothea Lange. The film's question — how're ya gonna keep her down on the farm after she's seen D.C.? — is answered when Jane returns home to her husband's loving arms. She is finally able to appreciate a rural sunset, in this artful document of a vanishing age.

Very few talking pictures are included here, but one is the collection's most poignant oddity. In a 97-sec. news clip, Offers Herself as a Bride (1931), a reporter interviews pretty Mary Clowes of New Eagle, Pa., who made headlines by declaring she would marry any man for $10,000. She explains the circumstances that drove her to this decision: her parents are to be evicted; her mother is a cripple, father old and infirm; one of her brothers died in a mining accident, the other was killed when a chimney fell on him!

Offers Herself as a Bride could be a prototype of a modern TV staple: the parading of misery. Yet Clowes carries herself with an unself-pitying poise, noting at the end that she has received thousands of offers but hasn't yet chosen her mate. Like Helen Holmes and other can-do Hollywood heroines, she has identified her problem and found a very American way of solving it — in the marital marketplace.