Working as a wildlife photographer in Kenya's game reserves in the 1960s, Norman Myers would idle away the days' hottest hours — when lions and elephants rested — by reading up on biology. He soon began to wonder why none of his books gave good estimates of the rate at which species were going extinct. So he did the calculation himself. While conservationists of the day guessed that the planet might be losing one species per year, Myers' research in the early 1970s revealed that the rate was probably closer to one species per day.

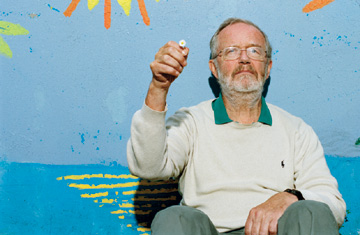

To Myers, by then a Ph.D. student in California, it was already clear that science is only as meaningful as the problem it tackles. "Most scientists are content to find new answers to existing questions," says Myers, now 73 and based in Oxford, England. "I've made a career out of raising new questions."

Among his accomplishments, Myers' research into what he dubbed "biodiversity hotspots" — small regions that are home to a disproportionately high number of species — provided a framework for conservationists to prioritize their work. Equally groundbreaking, he tallied the number of what he called "environmental refugees" — people fleeing areas because of, say, water shortages or desertification. And he continues to campaign with compelling logic against "perverse subsidies": the trillions of dollars governments spend on activities with steep environmental costs, like overfishing or fossil-fuel extraction.

The secret to his influence, says Myers, is to "specialize in being a generalist." Indeed, his range of interests and projects has always been dazzling. He has done research for organizations as diverse as the World Bank and NASA, has served as a consultant on the environment to governments and corporations, has lectured around the world, and has written some 20 books. There are two common threads in all of this work: a powerful conviction "that scientists should reach out to the general public," and a genius for inspiring laymen and experts alike to think anew.