The expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492 by command of the Inquisition

Sarah Palin must have hoped that her Jan. 12 video statement would silence her critics, who, in the wake of the Tucson, Ariz., shootings, have accused the controversial politician of contributing to the vitriolic rhetoric that plagues U.S. politics. But then Palin decided to describe the attacks leveled against her as a "blood libel." The phrase has a long, grim legacy tied to centuries of European persecution of Jews. Bigoted superstition had it that Jews needed the blood of heathens for various ritual practices. Within hours of the statement's publication and the video's appearance on Facebook, the Anti-Defamation League criticized Palin's message, saying that while blood libel "has become part of English parlance to refer to someone being falsely accused, we wish that Palin had used another phrase, instead of one so fraught with pain in Jewish history."

On the other hand, a group called Jewish Americans for Sarah Palin declared that "the use of the term blood libel is appropriate." Meanwhile, on the website Big Government, Alan Dershowitz of Harvard Law School said the term "has taken on a broad metaphorical meaning" and that "there is nothing improper and certainly nothing anti-Semitic in Sarah Palin using the term to characterize what she reasonably believes are false accusations."

The term Palin invoked to defend herself has deep roots in the demonization of the Jewish community throughout history. Apion, a 1st century B.C. Greek grammarian in the city of Alexandria, wrote that his Jewish neighbors "contrive each year at a certain time to capture a Greek foreigner, fatten him up, and then bring him to a certain forest, where they slay him with religious rites." Incendiary rumors like this one — Apion goes on to describe how the Jews eat the man's entrails — precipitated years of sectarian violence in ancient Alexandria, then one of the world's great cosmopolitan centers.

The advent of Christianity forever twinned Jews with blood. In the Gospels, Pontius Pilate publicly washes his hands of the guilt of committing Jesus to death, letting the assembled Jews take on the burden. "His blood be on us and on our children," they declare in Matthew 27: 25. These were words that stuck. Christendom grew rich by encouraging pilgrimages to venerate the purported remains of saints — bones, fingers, ears — but the Jews living in its midst were often openly faulted for bloody, occult practices, all of which were false.

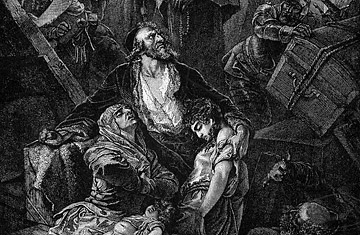

Medieval lore abounds with tales of Jews in towns across Europe, from England to modern-day Slovakia and lands farther east, stealing young Gentile children for blood sacrifices. Invariably, such sensational stories were told to justify mass executions and pogroms of Jewish communities. According to some histories, a 2-year-old named Simon in the Italian town of Trento disappeared in 1475 and was found in the basement of a Jewish family, his body drained of blood so that the Jews could make matzah bread for Passover. Records show that at least eight Jews in the town were subsequently executed; Simon would be canonized as a saint a century later. Fears of Jewish baby snatching were raised by the Spanish Inquisition, leading in part to the expulsion of the entire Jewish community from Spain in 1492.

These tales lingered well into the 19th century and even the 20th century, with anti-Semitism still particularly strong in stretches of Eastern Europe. But some of the first instances of occasions when governments publicly defended Jews from these "blood libels" took place in the Muslim world, with firmans, or edicts, issued as early as the 1400s by a series of Ottoman Sultans, preventing the trial of Jews on such unfounded, outlandish accusations. (Of course, the Middle East wasn't free of anti-Jewish violence. In 1910 the Jewish quarter in the Iranian city of Shiraz was sacked by rioters who were inflamed by fabricated reports that Jews had ritually killed a young Muslim girl.)

Since the Holocaust and the creation of the state of Israel, fables of Jewish demonry have thankfully — though not entirely — faded from the public conversation. And the phrase blood libel has come into frequent use, often by Jews invoking a whole history of persecution and injustice. In 1984 TIME was taken to court by Ariel Sharon, then a former Israeli Defense Minister, following a controversial cover story about the 1982 Israel-Lebanon war. Sharon claimed that it was a "blood libel" against Israel and sued TIME over a paragraph in its story about an official Israeli report on the 1982 slaughter of hundreds of Palestinians in the Sabra and Shatila by Christian Phalangists in refugee camps in Lebanon. The jury found that TIME had not libeled Sharon, based on the U.S. legal standard of "actual malice," but chastised the way in which the story was produced. Sharon said he was vindicated.

Palin was not the first person to dredge up the term in Tucson's aftermath — that would probably be conservative pundit Glenn Reynolds, who penned a Jan. 10 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal titled "The Arizona Tragedy and the Politics of Blood Libel," which critiqued the supposed politicization of the killings by liberals. Palin's video echoes this argument, labeling alleged shooter Jared Loughner as "deranged" and "apolitical," while making an appeal to the values of freedom of speech as enshrined by the First Amendment. The killer's act, she seems to say, should not be used to vilify a whole bloc in American politics. Fair enough. No community deserves to be demonized. But as an article in Slate argues, that's not a courtesy Palin and some of her supporters have extended to all.