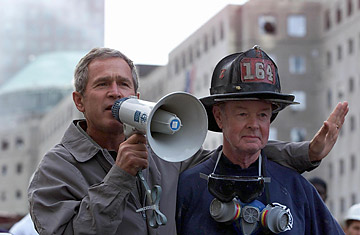

Former President George W. Bush, left, speaks to volunteers and firemen as he surveys the damage at the site of the World Trade Center in New York, September 14, 2001.

When Jared Loughner took the lives of six Americans and wounded Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords outside a Tucson supermarket on Jan. 8, he set in motion one of those increasingly rare intervals in American politics when the official partisan back-and-forth is put on hold for a period of national mourning. It is at those moments when the president is expected to fulfill one of his most essential — though unofficial — roles: mourner-in-chief. When the decision was made to hold a memorial ceremony on Jan. 12 at the University of Arizona's McKale Center, it was a foregone conclusion President Barack Obama would attend to deliver remarks, as his predecessors had done at similar moments.

In the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks, President George W. Bush won over the country just eight months after entering office on the basis of a disputed election with a demeanor both grief-stricken and heated. While he didn't return to Washington until the evening of the attacks, Bush eventually earned plaudits for his fiery bullhorn-toting performance at Ground Zero, and for stirring speeches at the National Cathedral and in front of Congress. While speaking before that joint Congressional session, Bush even held up a medallion of one of the fallen policeman in an embrace of national symbolism. "The president is not just the prime minister, he's also the king," says presidential historian Robert Dallek. "And he has to be a healing force to speak to the grief."

Though the non-administrative capacities of the commander-in-chief were not set out in the Constitution, the tradition of forging an intimate relationship with the American people goes all the way back to George Washington. His administration conducted an internal debate over whether the nation's leader would even attend funerals in an official capacity, says George Mason University presidential historian Richard Norton Smith. "This was all confronted in the very beginning, and it's been settled [in the affirmative] ever since."

Many decades later, when faced with a civil war that threatened the very existence of the country, President Abraham Lincoln famously opted to respond with the soaring rhetoric of the Gettysburg Address, a speech delivered at a place of great sorrow. "We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live," Lincoln said while standing on the blood-drenched battleground. But it was the dedication of the first unknown soldier on Nov. 11, 1921 that established the modern pageantry of national mourning, says George Mason's Smith. President Warren Harding presided over a Washington procession and internment at Arlington National Cemetery attended by former presidents Woodrow Wilson and William Taft, by that point Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

In the U.S., the act of grieving war dead or the victims of a mass shooting rarely attracts mainstream political opposition. Yet the events surrounding a memorial cannot be totally divorced from political considerations. "When an office holder tells you something's not political, it's nonsense," says Dallek. Lyndon Johnson's performance in the days following the assassination of John F. Kennedy was seen as particularly masterful in cementing his legitimacy as president. "When Johnson said to the nation, 'All I have I would have given not to be here today,' that really resonated as someone sharing the grief." Humility was the tone of choice for Obama, when he spoke in the aftermath of the 2009 Fort Hood shootings that killed 13. He didn't focus on religious affiliation, the topic which dominated the airwaves after it came to light that the perpetrator was Army Maj. Nidal Hassan. Instead, the President gave short biographies of the victims, saying, "We must pay tribute to their stories."

Indeed, the biggest challenge for a president in such moments is toeing the line between proper mourning and exploitation of grief. After the death of Commerce Secretary Ron Brown in a 1996 plane crash, Bill Clinton was pilloried by his critics for being insincere when a photo emerged of him smiling as he left the funeral. But just the year before, Clinton's speech after the Oklahoma City bombing, in which he spoke of a "duty to purge ourselves of the dark forces which gave rise to this evil," was so pitch perfect that Obama's performance during the current crisis is being referred to as his "Oklahoma City" moment.

There's more than a little stagecraft involved, says Smith. "Reagan said half-joking that he couldn't imagine someone doing the job who wasn't a bit of an actor. It's all about political theatre. After the explosion of the Challenger, he raised the bar and set the standard in a speech that contributed to the Reagan legacy." Speaking from the Oval Office, Reagan offered a defiant pledge to continue space exploration in honor of the seven Challenger victims. "We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and 'slipped the surly bonds of earth' to 'touch the face of God," he said. Because of their overexposure, says Smith, the modern presidents do not benefit from the cachet that once came with selective public appearances, save for special moments. "Even though we see the president all day on television and on the Internet, there are still a few occasions that the office has a unique hold on people."