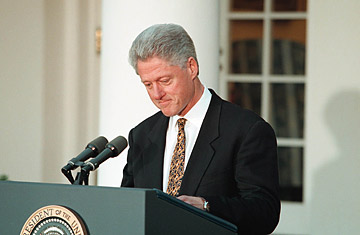

Bill Clinton

As Illinois lawmakers debate the likely impeachment of Gov. Rod Blagojevich — who has repeatedly ignored calls for his resignation — the country has another impeachment on its mind: ten years ago Dec. 19, President Clinton was impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives for obstruction of justice in a trial related to his Oval Office dalliances with Monica Lewinsky.

Clinton was impeached by congress, but never actually removed from office. This is because impeachment is a two-step process and although it is taken very seriously — only seventeen federal officials have ever been impeached — it's really nothing more than a formal decision to commence a trial, in which a conviction would automatically remove the official from office. (See pictures of Presidential First Dogs.)

England came up with the idea of impeachment; in medieval times, any English subject or politician could initiate impeachment charges in Parliament. But by the fourteenth century, Parliament decided to limit the privilege to its own members. Four hundred years later, in the newly independent United States of America, Constitutional Convention delegates debated over how to include the process in the Constitution. In England, Parliament tended to impeach politicians it didn't like, regardless of offense — but the Constitution's creators didn't like this, and decided to limit impeachment only to crimes of treason and bribery. Virginia convention delegate George Mason suggested that the term "high crimes and misdemeanors" be added to the list of impeachable offenses (in 18th century England, a "high misdemeanor" normally meant a crime against the state, such as abuse of power or neglect of duty). However, the vague wording was never strictly defined and has been the subject of many long, legal debates.

Here is how the process works: the House of Representatives votes on whether to start an inquiry into the possibility of an impeachment. It forms a special committee to gather information and evidence (or, in the case of Clinton, reviews the Starr report). The committee then presents the information to the House, which mulls over the evidence and votes on whether or not to impeach. If the vote passes, a formal trial is held in the Senate. If the Senate finds the official guilty of any of the House's charges, he or she is booted from office. (If this sounds boring, just read the above paragraph like it's a Schoolhouse Rock song.)

Tennessee Senator William Blount was the first person impeached — in a manner of speaking. In 1797, Congress found out that Blount had been conspiring with the British to take Florida and Louisiana from Spain, and the House immediately voted to impeach him. The Senate was so excited to get rid of Blount that it forgot to hold the trial and instead just voted him out of office. When the Senate realized its own error it was too late; the government couldn't decide to remove him from an office he no longer retained. Instead, the Senate cut its losses and considered the matter closed.

Congress tried the process again in 1804, when it voted to impeach Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase on charges of bad conduct. As a judge, Chase was overzealous and notoriously unfair; he ordered a Revolutionary War veteran hanged for treason after he refused to pay taxes, and he found the author of a book critical of President John Adams guilty of sedition. But Chase never committed a crime — he was just incredibly bad at his job. The Senate acquitted him on every count.

It did, however, oust John Pickering from office that year. The mentally unstable, alcoholic New Hampshire judge was frequently drunk at work and sometimes failed to show up at all. During his trial, he even challenged President Jefferson to a duel. After a short debate to consider whether Pickering was mentally fit for trial, the Senate voted 20-6 to remove him.

Abraham Lincoln went to the theater one night in 1865, and Andrew Johnson became President the next morning. Because Johnson hadn't been elected to office, Congress became very angry whenever he vetoed a bill — who did he think he was, anyway? — and in 1867 the House Judiciary Committee drew up a long list of complaints about him and recommended that he be impeached. The vote never passed and was shelved until 1868, when Johnon fired a political rival, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton — in violation of the Tenure of Office Act, which said that the President couldn't remove a Senate appointee without the Senate's approval. The House voted to impeach, and the Senate came very close to agreeing — Johnson clung to the Presidency by just one vote. But in the following election he failed to win his party's nomination and ended up serving out less than one term, which technically wasn't even his.

The federal government ran fairly impeachment-free for the next century or so — a corrupt judge here, a kickback-receiving Secretary of War there — until the epochal undoing of President Richard Nixon, who avoided the indignity of being called to account for the Watergate conspiracy by resigning before Congress had a chance to impeach him. Then, in 1998, came President Bill Clinton, with the Blue Dress and the cigars and the statement, "I did not have sexual relations with that woman."

Despite the hundreds of uncomfortably frank papers in the report compiled by independent counsel Kenneth Starr, Clinton was impeached on one count: lying under oath about the nature of his relationship with Monica Lewinsky. Indignation over immoral acts in the Oval Office and the counterargument of a "vast right-wing conspiracy" (as First Lady Hillary Clinton darkly hinted) were all anyone could talk about in 1998. And although there had been rumors of impeachment for months leading up to the vote, no one really thought it would happen. Clinton was acquitted in the Senate, served out his term in office and went on to a successful post-White House career as a humanitarian, public speaker and international wheeler-dealer. But covering up an extramarital affair and selling a U.S. Senate seat, as Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich is accused of doing, are entirely different matters. When the Illinois State House of Representatives finishes its inquest and holds a formal vote, Blagojevich may not get off as lightly.

See TIME's Person of the Year, People Who Mattered, and more.