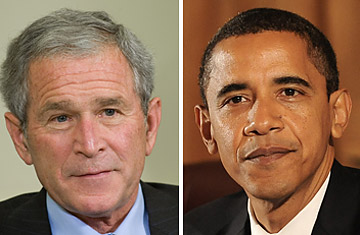

President George W. Bush, left, and President-elect Barack Obama

Americans like to think they perfected the peaceful transfer of power from old regime to new: no crimes, no coups, no blood in the streets. But that doesn't mean the future Former Leader of the Free World has an easy time handing over the keys to the White House. It's not just ego that has a way of fouling up this transition; both parties have one eye on the history books, as the outgoing President airbrushes the epilogue and the arriving one prepares the prologue. (See pictures from the White House Photo Blog.)

President-elect Barack Obama has at least some advantages in his first meeting with President George W. Bush at the White House on Monday. In the history of handovers, things usually go a little more smoothly if the outgoing President is leaving by choice or constitutional mandate rather than if he has just been crushed on the field of electoral battle. While Obama ran against Bush's record, he never played to the personal loathing that animates many on the left; and Bush, by remaining at an undisclosed location throughout Campaign 2008, seldom had a bad word to say about Obama.

That alone distinguishes them from past Presidents sharing the secret handshake, but Bush has also been uncommonly gracious for a departing POTUS. "Ensuring that this transition is seamless is a top priority for the rest of my time in office," Bush said in his Saturday radio address. "My Administration will work hard to ensure that the next President and his team can hit the ground running." (See pictures of Barack Obama's campaign behind the scenes.)

This election, given the circumstances and transformational mood, has been compared to Franklin Roosevelt's ouster of Herbert Hoover, another transition that occurred amid economic carnage. Happily for all concerned, this time both the incoming and outgoing President appear inclined to play nicer than their predecessors did.

It didn't help in 1932 that the two men neither liked nor trusted each other: Hoover called Roosevelt a "chameleon on plaid," while F.D.R. preferred the image of Hoover as a "fat, timid capon." In the final days of the campaign, Hoover denounced Roosevelt's "nonsense ... tirades ... glittering generalizations ... ignorance" and "defamation" on his way to losing to him in 42 of 48 states. Since Inauguration Day was not until March 4, 1933, and with the global financial system in tatters, there was urgent need for action — but Hoover's efforts to reach out to Roosevelt in the name of bipartisan cooperation were dismissed by critics as his trying to reverse the election results and force Roosevelt to agree to an agenda that would have effectively gutted the New Deal. Hoover's defenders, meanwhile, saw him as a "man on the verge of victory," notes biographer Richard Norton Smith, "who had arrested the downward spiral only to see it slip out of control through the irresponsible behavior of his successor."

Their first visit after the election was not promising: Roosevelt came for what he thought was a personal call at the White House on Nov. 22, 1932 — only to find Hoover's Treasury Secretary on hand to help the outgoing President deliver a lecture on the importance of the gold standard, the stability of the banking system and the problem of Europe's war debt. When it was over, Hoover judged Roosevelt to be "amiable, pleasant ... very badly informed and of comparably little vision." (See pictures of election drama.)

But the world would not wait, and as the Inauguration approached, Hoover tried to force Roosevelt's hand: he wrote to enlist his help in calming investors; and he told a colleague that Roosevelt was a "madman" for not listening to him or lifting a finger to forestall a banking crisis, which began in mid-February. It guaranteed that Roosevelt took the oath of office amid such an atmosphere of crisis that Hoover had become the most hated man in America. There were rumors, as he left Washington, that he had been arrested trying to escape aboard Andrew Mellon's yacht with the gold he had raided from Fort Knox.

It would be 20 years before the Democrats had to hand power back; this time the incumbent President was Harry Truman, looking to ease the transition of his former friend and then President-elect Dwight Eisenhower. This one didn't go well either. Despite the fact that the two leaders had worked together closely during the final days of World War II and in the creation of NATO, the 1952 campaign had strained relations to the breaking point. Truman thought Eisenhower had sold his soul when he wouldn't denounce Joe McCarthy on the stump: "I thought he might make a good President," Truman said at the time, but "he has betrayed almost everything I thought he stood for."

After the election, relations weren't much better. Truman wrote in his diary on Nov. 11, 1952, that Eisenhower was being coy about cooperating on the transition. "Ike and his advisers are afraid of some kind of trick. There are no tricks ... All I want is to make an orderly turnover. It has never been done."

And yet eight years later, when it was Eisenhower's turn to hand over the keys, he was conscious of the price of a bad transition and determined that this one would proceed more smoothly. That was surprising in its own way, since 1960 saw a change not just of party but of generation, from the oldest President in history to the youngest. John F. Kennedy viewed Eisenhower as antique, out of step; he referred to him as "that old a-hole." Eisenhower for his part saw Kennedy as callow and unready; "I will do almost anything to avoid turning my chair and country over to Kennedy," he told his friends during the campaign.

Their first meeting, on Dec. 8, 1960, went an hour longer than planned. They talked of Berlin, the Far East, Cuba and various world leaders. Much of the talk was about the structure of decision-making — especially on national security issues. Eisenhower told his friends that Kennedy had little understanding of the presidency. But on other matters, Kennedy had "tremendously impressed him;" he described him as "one of the ablest, brightest minds I've ever come across." And Kennedy told his brother Bobby that he was struck by the sheer force of Eisenhower's personality. He admitted that Ike was "better than I had thought." On his first day in office, Kennedy made his gratitude official: "I am sure that your generous assistance has made this one of the most effective transitions in the history of our Republic." He would find himself calling on the former President both when he needed some public cover after the Bay of Pigs and when he needed private guidance for the Cuban missile crisis.

Former Presidents tend to rise to the occasion when the call comes from the Oval Office, even if the caller is a former adversary. It is an act of patriotism and perhaps pity from men who, knowing what the job entails, are uniquely positioned to help. Barack Obama has an interesting array of predecessors to choose from: Jimmy Carter, the acclaimed humanitarian who has seemed at times to delight in tormenting his successors; Bill Clinton, whose own chapter in history has some extra footnotes now with Obama's win; and two Presidents named Bush, one with a more recent feel for just how crushing the job will be, the other with perhaps more useful advice in how to manage it.