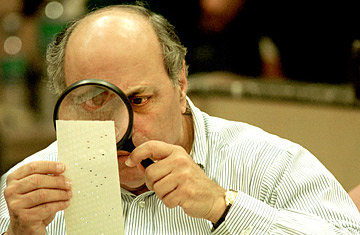

Judge Robert Rosenberg of the Broward County Canvassing Board uses a magnifying glass to examine a dimpled chad on a punch-card ballot during a vote recount in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., on Nov. 24, 2000

Like a man revisiting the scene of a bad car wreck, former Vice President Al Gore came to Palm Beach County, Fla., on Friday. Palm Beach, you may recall, is where butterfly ballots, hanging chads and other election catastrophes helped thwart Gore's efforts to win Florida's electoral votes — and the presidency — in 2000. That bizarre recount drama gave the White House to George W. Bush by just 537 ballots. This time Gore was stumping for Barack Obama, but memories of the 2000 debacle were surely not forgotten, especially since Palm Beach keeps experiencing electoral mishaps. The county is using a third voting technology in as many presidential elections, and its first two outings this year weren't encouraging: 697 votes uncounted in one municipal election, and 3,500 missing during the recount of a judge's race.

That doesn't mean Florida — the nation's largest swing state, with 27 electoral votes — is again headed for a 2000-style disaster. The Sunshine State seems to have instituted enough changes since then, like requiring optical-scan voting machines that provide real paper trails, to make a meltdown of that magnitude unlikely. But that's not to say that Florida in 2008 won't see a presidential vote as close as 2000's. Obama does have an unexpected lead (of an average of about 4 points) over John McCain in the Florida polls. Yet it's narrow enough, and the number of independent voters — almost 20% of the state's electorate — is vast enough, to make this another Panic on the Peninsula, for which every vote matters. "Florida," Gore warned, "can once again decide the outcome of a national election."

This kind of neck-and-neck finish would put a tremendous strain on any state's electoral infrastructure (see Ohio in 2004). So the question looming like Spanish moss in Tallahassee is, Has Florida girded itself adequately since 2000 to keep whatever cracks haven't been fixed — especially in trouble spots like Palm Beach — from turning a tight race into a real mess?

The good news is that Florida's current governor, Republican Charlie Crist, is driven more by common sense than by ideology. After taking office last year, he scrapped the antiquated punch-card ballots (e.g., the butterfly ballot) as well as the flawed touch-screen voting machines favored by his conservative predecessor, Jeb Bush (the President's brother, who was governor from 1999 to 2007). A big reason: in a 2006 congressional race in Sarasota County, an incredible 15% of ballots cast on touch-screen machines registered no choice at all — in a race decided by a razor-thin margin of 386 votes. All 67 Florida counties have now adopted some form of a paper-ballot optical scan, in which votes are marked on a sheet and electronically tallied. Crist's move "was a giant step in the right direction," says Dan McCrea, head of the Florida Voters Coalition. It has also led to a more uniform voting system instead of the chaotic county-by-county melange of 2000.

Another Crist dividend: Kurt Browning, his appointed secretary of state, who oversees elections, is actually an elections-management professional. Few can forget the secretary of state under Jeb Bush, Katherine Harris, who oversaw the 2000 recount. Harris, Florida's last elected secretary of state, had no elections expertise and looked all but clueless when the chads hit the fan. Worse, her pledge of impartiality seemed laughable given that she was the George W. Bush campaign's Florida chairwoman. Browning, who like Crist has proved to be a more bipartisan operator than his predecessors, spent 26 years as a county elections supervisor, was president of Florida's Association of Elections Supervisors and was one of the state's point persons for the federal Help America Vote Act of 2002.

But this is still Florida, after all, and the potential for a breakdown has to be considered. Optical-scan technology is relatively reliable, for example, but it's also slower — some delays due to technical glitches with the new machines were reported during Florida's early voting — and with expected turnout approaching 80% in Florida, voting-rights advocates worry about congestion and overload. Stoking the anxiety is a shortage of poll workers in larger counties like Broward, where Fort Lauderdale is located. And McCrea warns that the Florida legislature hasn't provided for enough mandatory post-election vote audits. (It requires routine scrutiny of just one race — such as for President or a congressional contest — in each county, and for only 2% of the precincts at that.) "Routine scrutiny in the voting system is as important as it is in banking or airline maintenance," says McCrea. "If not, optical scan just gives us a paper trail to nowhere."

A bigger worry is Florida's central voter database. In a state whose residents are as transient as Florida's, concerns about who is eligible and ineligible to vote are always acute — especially since Florida now has a "no match, no vote" law that tightens voter-identification requirements at the polls. The database against which IDs are checked failed miserably in 2000, when thousands of appropriately registered voters, especially African Americans, were turned away at polling sites. (Many were mistakenly pegged as convicted felons, who at that time were ineligible to vote in Florida even after serving their sentences; Crist has since made it easier to restore felons' voting rights.) Controversy arose again in 2004, when secretary of state Glenda Hood tried to purge 47,000 names from voter rolls — because the database, again mistakenly, told her that many people were ineligible — before county supervisors intervened.

Browning's office insists it has had enough time to correct the database flaws, but watchdogs argue that it's hard to tell because the process hasn't been transparent enough. Either way, it's a troubling issue this year for two reasons. First, Florida has had a deluge of more than a million new registered voters since 2004, and almost half of them have come in 2008 alone, leading many to wonder if the database has been able to keep up. And Florida's spiking home foreclosures spell the risk of thousands being stricken from the rolls simply because their new address (or lack of one) suddenly doesn't match what's on file. Voters removed from the rolls get a provisional ballot that county elections supervisors are supposed to verify later; but in 2004, Florida ended up counting only 36% of the provisional ballots cast, far below the national average.

But a good gauge for potential electoral trouble in Florida — the level of lawyer activity — doesn't seem to forecast a tropical vote storm. Mind you, the lawyers are out in force, as they always are here, but they aren't yet expecting a major fight. "I don't think there is anything that is visible at this time that we can anticipate would be materially contestable," says Barry Richard, the Tallahassee attorney who represented Bush during the 2000 recount but isn't representing any side this time. (Richard, ironically, is a lifelong Democrat who is voting for Obama.) "Florida could be close," he adds, "[but] it doesn't look like it's all going to rest on a single state. McCain has an uphill battle in a bunch of states. Going into the 2000 election, it was tight all over the place." True enough. But fair or not, when things get tight in Florida, Americans instinctively brace for a car wreck and its long-lasting damage.

— With reporting by Hector Florin / West Palm Beach and Siobhan Morrissey / Miami