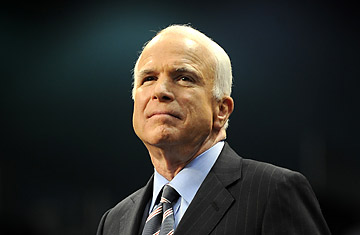

John McCain speaks at a campaign rally.

Almost 12 years ago to the weekend, Bob Dole let loose.

He was losing the presidential election to President Bill Clinton and he knew it, so he decided to end his campaign in style, thaw his icy relationship with the press, and start having fun. "He'd rumble back to the back of the plane, and we'd hear the laughter up in the front," remembers Sheila Burke, Dole's former chief of staff. "There was a looseness about it."

One of the old friends Dole brought on board to celebrate the last 96 hours was Sen. John McCain, who still remembers those days as a highlight of his political life. "He was unleashed," McCain fondly recalled of Dole, during an interview in the spring of 2007. "He knew he was going to lose."

More than a decade later, McCain now finds himself in a position that appears not too dissimilar to Dole's in 1996. Swing state polls suggest that he is sharply behind in several key swing states, his campaign crowds remain less than overwhelming, and Obama has been outspending him on the airwaves by a margin of 3 to 1. Despite a tightening in some local polls, national tracking polls — which the McCain campaign cited as evidence that the race was getting closer — have begun to widen again.

But McCain is refusing to take the path of Dole. In fact, McCain's underdog role seems to have hardened the resolve of both McCain and the staff around him. Where Dole chose to make the final days of the campaign a celebration with friends, McCain remains focused on the prize, with a fierce intensity that continues to rouse his audiences. "I'm an American and I choose to fight," he calls out at every campaign stop, drawing cheers from the crowds, which tend to number no more than several thousand.

McCain's staff continues to point to public polling data that shows any glimmer of hope. There are no winks or nods on the campaign bus suggesting the race has been lost. There has been no thaw in McCain's frosty relationship with his traveling press. "We are not just flying around the country for the hell of it," says Mark Salter, one of McCain's closest advisers. "This is a winnable race. We feel we've been gaining since Thursday and we can catch him by Tuesday."

Salter pointed to a recent Mason-Dixon poll that suggested the race had tightened since mid-October in Florida, a crucial state for McCain, with Obama's lead narrowing to just two points. (Other recent polls have shown the Obama lead as big as 7 points in Florida.) McCain has also recently retaken the lead in a Real Clear Politics average of polls for Missouri, where the race is essentially tied. The race has also narrowed in public polling of Pennsylvania, which McCain is targeting with events on Saturday and Sunday. Obama led in the state by an average of 14 points in mid-October. His lead is now less than 8.

Dole, by contrast, faced numbers much more dire than McCain in the final weeks of his race. A 1996 Gallup tracking poll found Dole with just 35% of the national popular vote on the eve of election, compared to 51% for Clinton and 8% for Ross Perot. On election day, Dole carried 19 states and 41% of the vote, compared to Clinton's 31 states and 49% share.

Perhaps the most striking feature of McCain's late stage campaign is his ferocity on the stump. For much of the spring and summer, McCain favored town hall meetings, often struggling with teleprompters. His tone was more often conversational. Today, the teleprompter has become a regular part of his routine, and his performance borders on bombastic. The closing stump speech is a mixture of conservative ideology on taxes, questions about Obama's truthfulness, and jokes about Obama's gaffe-prone running-mate, who McCain refers to as "Joe the Biden" and "the gift that keeps on giving."

In introductions on the stump, South Carolina Sen. Lindsay Graham, who is one of McCain's closest friends, calls the Republican nominee "John The Fighting McCain." This fighting motif, which McCain debuted at the end of his convention speech in Minneapolis, now occupies the thematic center of McCain's message. "Stand up, stand up, stand up and fight. America is worth fighting for. We never give up. We never quit," he calls out at the end of each rally, raising his voice and building the excitement of the crowds.

When McCain first delivered those lines in his convention speech, he seemed to struggle with the rhythm. Salter, his speechwriter and adviser, sat in the front row at the convention hall urging McCain not to stop the delivery as the crowd noise built. Today, McCain delivers the same words with a verve and confidence that seemed previously lacking. He enters the final 96 hours of the campaign facing down extraordinary headwinds, aiming for one of the most unlikely electoral upsets in U.S. history. It is the underdog position that McCain has long embraced, and the old warrior shows no sign of letting up now.