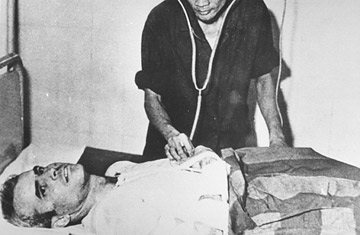

Senator John Mccain In A Hanoi Hospital During The Vietnam War.

When he first ran for Congress in Arizona nearly three decades ago, John McCain had one clear liability: he wasn't from the state, and he could count the number of years he had lived there on a couple of fingers.

So his primary opponent, state senator Jim Mack, attacked him as a Johnny-come-lately. To counter the charge, at a candidate forum, McCain offered a decidedly pointed response. "I wish I could have had the luxury, like you, of growing up and living and spending my entire life in a nice place like the first district of Arizona, but I was doing other things," he said. "As a matter of fact, when I think about it now, the place I lived longest in my life was Hanoi."

McCain's heroic biography, as a Navy veteran and former prisoner of war, gave him a clear out for the carpetbagger critique. It was widely seen as a devastating response — and a key turning point in McCain's early political career.

Twenty-six years later, McCain has returned to the same tactic, but some critics say he is overplaying his trump card. At several points over the past two weeks, the McCain campaign has raised his military service in efforts to defuse political attacks, even when it seemed to have little if any bearing on the issue at hand. When the Obama campaign laid into McCain for not knowing the number of houses owned by his family, McCain spokesman Brian Rogers told the Washington Post that "this is a guy who lived in one house for five and a half years — in prison," a refrain McCain himself repeated more recently during an appearance on The Tonight Show. When an Obama staffer suggested, without evidence, that McCain might have left the "cone of silence" before a forum at Rick Warren's Saddle Creek Church, McCain spokeswoman Nicole Wallace said, "The insinuation from the Obama campaign that John McCain, a former prisoner of war, cheated is outrageous." And in a speech this week questioning Obama's foreign policy judgment and interpretation of the end of the Cold War, McCain himself mentioned, "Now I missed a few years of the Cold War, as the guest of one of our adversaries."

The McCain campaign is unapologetic about the tactic, which speaks to the complex ways that McCain has referred to his military service over his career. On the one hand, his time in captivity in Vietnam was clearly the most defining experience of his life, but he has often been hesitant to discuss the experience at length. He has always made clear, including at the start of this presidential run, that he wanted to move beyond the experience, something he has done with great success.

Mark Salter, a close McCain adviser and biographer, says there is nothing wrong with the growing role McCain's military service is playing in the campaign, a biography that is sure to be on full display next week at the Republican Convention in St. Paul, Minn. "Every nominee tells their story," Salter says. "Obama talks about his service as a community organizer. Neither we nor the press begrudge him that. And John gets to tell his story of service. Why anyone would argue he shouldn't is beyond me."

But critics say the issue isn't the McCain campaign's use of biography per se, but rather how and when they bring it up. By turning to his POW experience in order to deflect any question, be it about his character, wealth or memory, McCain appears to risk trivializing his own heroic personal story in much the same way that Rudy Giuliani's constant invoking of 9/11 became the butt of jokes during his presidential campaign.

Of course, the McCain campaign may simply realize that, when it comes to such a moving tale of personal sacrifice as the candidate's years of captivity, there is no danger of going to the well too many times. As conservative commentator Pat Buchanan remarked on MSNBC earlier this week, they keep doing it because it keeps "working."

Indeed, from the beginning of the campaign, McCain has consistently made his time in captivity a feature of his stump speech. On tours through New Hampshire and Iowa, he told a cycle of stories: a tale about a prison mate who was caught and beaten for sewing an American flag, and one about a North Vietnamese prison guard who drew a cross in the dirt to demonstrate to McCain his Christian faith. He has also described in some detail the painful rope bonds that his captors would tie him in overnight.

But McCain has also made clear that he does not want Vietnam to be the "leitmotif" for the rest of his life. In his memoir, Faith of My Fathers, McCain describes this in some detail. "My public profile is inextricably linked to my POW experiences. Obviously, such recognition has benefited my political career, and I am grateful for that," he writes. "But I have tried to make what use I can of Vietnam and not let the memories of war encumber the rest of my life's progress. Neither have I been content to accept that my time in Vietnam would stand as the ultimate experience of my life."

Next week, the Republican Party will host a four-day celebration of McCain's life and experience, an event that is sure to focus on McCain's time as a Navy flyer and POW. It's a compelling storyline his campaign has no plans to run away from or leave behind, even if his opponents would like it to backfire.