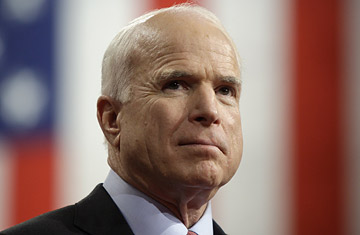

Republican presidential candidate John McCain

John McCain has retooled his campaign — yet again — and put Steve Schmidt, a veteran of Karl Rove's old shop, in charge of the day-to-day operation. He's back out again doing what he says he loves best, mixing it up with voters in town hall settings. Where he once professed not to know much about the economy, it's now what he talks about constantly. But in spite of all the changes, there is still one key hurdle that McCain has yet to overcome, something a supporter in Portsmouth, Ohio, summed up pretty neatly in one of those question-and-answer sessions with the presumptive Republican nominee at the local high school: "When are you going to go out and say, 'Read my lips. I am not the third term of Bush?'"

McCain quickly launched into the ways his own presidency would differ from that of the last eight years, starting with his pledge to cut spending and balance the budget by 2013. He has yet, however, to back up that bold promise with the details of just of how he plans to accomplish it. And economists are skeptical that he can, especially if he also stays true to his commitment to extend the tax cuts that were George Bush's signature economic achievement.

As frequently as he now talks about economic issues, his attempt to embrace two conservative economic models at once isn't helping his credibility. On the one hand, McCain argues for fiscal discipline, with his promises to end wasteful pork-barrel spending (which he mentioned five times during his appearance in Ohio). On the other, with his commitment to tax cuts, he embraces supply-side economics, which maintains that short-term deficits don't really matter.

But does it really matter to voters if the numbers don't add up? Not necessarily, argues former Republican Congressman Vin Weber, an influential conservative voice. In a time of economic anxiety, "voters want to know the candidate, first of all, understands the seriousness of the problem, and second of all, they have to believe there's a commitment to change." Weber says what voters listen for are "big signal issues."

On that first front, McCain has faced some questioning this week for referring to the economy as simply "slowing." But he fared better when listening to voters' personal plights at the town hall gathering. Mary Houghtaling, who runs a hospice in Wilmington, Ohio, choked up as she told McCain of DHL's plans to close its domestic air hub in her town, a move that could throw 8,600 people out of work. "This is a terrible blow," McCain told her. "I don't know if I can stop it. That's some straight talk. Some more straight talk? I doubt it."

It was not the kind of answer you often hear from a politician, and McCain is certainly hoping that kind of change will impress voters. When I talked to Houghtaling after the event, she was still wiping tears from her eyes. Houghtaling noted that she had supported McCain when he ran for President in 2000, and she intends to do it again. "Had he been elected," she said, "I believe it would have been a different world." But she didn't fault McCain for his answer: "I think he was honest, because I don't think there's any hope."

Candor should certainly help McCain — to a degree. But in an election year, he and his team have more work to do honing their message if they want to emerge with more than a moral victory.