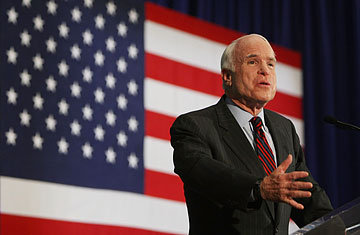

Republican presidential candidate and U.S. Senator John McCain speaks on June 3 in Kenner, Louisiana

Can a 72-year-old white male Republican who has served in Congress for more than a quarter century represent change to a nation that craves it? Can he win the White House in a year when his party is in widespread ill repute, and is led by the most unpopular incumbent President in the history of polling? And most importantly, can he do it against the youthful, multi-ethnic, charm-infused, walking, talking embodiment of change that is his Democratic opponent?

Tuesday night, John McCain, who turns 72 in August, began making the case that the answer to all those questions is yes. With Barack Obama running on the slogan "Change We Can Believe In," the four-term Senator from Arizona might have chosen to avoid the reform motif entirely, to run instead on "experience" or "leadership." But he and his campaign have decided they have no choice but to embrace the idea that voters want change above all. They also believe that Obama is the chimera of change, while McCain can actually deliver it. "This is, indeed, a change election," McCain said in New Orleans, the second time in two months that he's chosen that Katrina-ravaged city to make a point of distinguishing himself from George W. Bush. "But the choice is between the right change and the wrong change; between going forward and going backward."

The essence of McCain's argument tonight, and going forward, is threefold. First, he is trying to throw off the charge made by Obama and Democrats that a vote for McCain is a vote for a third Bush term. "Why does Senator Obama believe it's so important to repeat that idea over and over again?" McCain said. "Because he knows it's very difficult to get Americans to believe something they know is false...[T]he American people didn't get to know me yesterday, as they are getting to know Senator Obama. They know I have a long record of bipartisan problem-solving." He also has a long record of bucking his party and his President, which he pointed out tonight.

McCain is right about this. He's right that he has a far longer, far more substantive record of forging bipartisan consensus — and of resisting the demands of party loyalty — than does Obama. On the environment, energy policy, campaign finance, tobacco, torture, pork-barrel spending, immigration and more, McCain has repeatedly worked against his party or his President, or both. But the problem for McCain is that on the three issues that matter most to voters this year — the economy, health care and Iraq — it's hard to make the case that he is charting a course different from Bush's. Obama and Democratic surrogates will pound the idea that McCain is really McBush — and they'll use the now-famous photo of McCain embracing Bush during the President's 2004 reelection campaign to reinforce the point. "When this thing is over, every voter in America will see McCain hugging Bush in their dreams at night," says a Democratic strategist who advises the Obama campaign from the outside. "Or should I say nightmares?"

McCain's second objective is to rub some of the shiny gloss off Obama and encourage voters to see the presumptive Democratic nominee for what, Republicans say, his record shows he is — a conventional liberal proposing conventionally liberal solutions to the nation's problems. "The wrong change looks not to the future but to the past for solutions that have failed before and will surely fail us again," McCain said Tuesday. "I have a few years on my opponent, so I am surprised that a young man has bought in to so many failed ideas. Like others before him, he seems to think government is the answer to every problem; that government should take our resources and make our decisions for us. And that's not change we can believe in." The last line — a play on Obama's signature slogan — served as the speech's refrain.

Finally, McCain seeks to portray Obama as dangerously naïve and inexperienced in matters of national security. In New Orleans he picked up on the issue that he and his campaign have been using to attack Obama for the past several weeks — Obama's statement that as President he would be willing to meet with the leaders of Iran, North Korea, Venezuela and other rogue nations "without preconditions." Said McCain: "Americans ought to be concerned about the judgment of a presidential candidate who says he's ready to talk, in person and without conditions, with tyrants from Havana to Pyongyang, but hasn't traveled to Iraq to meet with General Petraeus, and see for himself the progress he threatens to reverse."

Since securing the G.O.P. nomination in March, McCain has spent his time raising money, reassuring uneasy conservatives and building, haltingly, a full-scale campaign operation for the race ahead. "We've also been watching Obama lose a lot," says a McCain adviser. "It's been instructive." The Democratic primary fight exposed Obama's weaknesses with downscale white voters, and white women generally — weaknesses McCain hopes he can exploit as the general election gets under way (which is why he threw a few verbal bouquets to Hillary in his speech). As McCain aides like to point out, their candidate has managed to stay nearly even with Obama in national polls — and very competitive in key states — despite the mammoth, three-headed albatross of Bush, the economy and the war that hangs heavily around his neck.

On paper, McCain made a reasonably strong argument tonight. But he didn't do himself any favors with his delivery. His presentation wasn't horrible, for him. But McCain is an awkward speaker at best; he's far better interacting with voters in a town hall or with reporters on the back of his campaign bus. He has none of Obama's formal oratorical skills — a contrast that will become only more glaring as the campaign progresses. McCain's hope is that Obama's superior speaking skills will dazzle pundits and other elites but won't translate into votes. "This is not a speech-making contest," Alex Castellanos, a G.O.P. consultant and outside adviser to the McCain campaign, said on CNN tonight. "Thank God!"