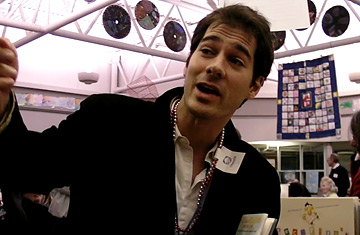

TIME correspondent Joel Stein attends a caucus at Westridge Elementary School in West Des Moines, Iowa.

The Iowa caucus is designed to answer the crucial question America has been asking for nearly a year: If old people, farmers and evangelicals chose the President based on their second and third choices, who would lead the free world?

Wanting to see democracy in whatever the opposite of action is, I walked into the Westridge Elementary School in West Des Moines to caucus. To my left, in a library full of Laura Ingalls Wilder books, the Democrats assembled for their uniquely convoluted system, which involves gathering next to the sign of your favorite candidate, hoping you can collect more than 15 percent of the voters in the room, trying to convince the followers of the least popular candidates to join you — and, most of all, re-explaining the rules every few minutes. To my right, in the unadorned gym, the Republicans sat in neat rows of folding chairs, wrote down the name of their favorite candidate and quietly waited for the winner to be announced. Like most Americans, I wanted to be a Republican and hang out with Democrats.

As soon as I walked into the library — which was overstuffed with 267 people compared to the 86 who came four years ago — I realized that Iowans are drunk with the power of choice. The rest of the country makes a selection between a few well-tested candidates. The people of Iowa are the early market research groups who feel duty bound to try every insane invention Burger King can think of. Everyone is way too into it, and someone in the room always argues that, if you really think about it, the Coq Au Vanwich is pretty good, or that Dennis Kucinich will make a fine president.

The Democratic rules only egged on the chaos, especially because there weren't any. I, for instance, was allowed to walk around during the voting process and talk to anyone I wanted. Out-of-state caucus tourists — the only group dorkier than fantasy league baseball owners — walked around freely. The first person I talked to, Margie Nelson, the Obama precinct captain, threw a set of plastic beads with an Obama tag around my neck. Wanting to be a good caucus goer, I offered to take off my top, but Margie suggested I refrain. She also made a huge batch of homemade cookies and brownies — the time-tested strategy to lure the supporters of candidates who don't get 15 percent— but the school janitor didn't permit any food in the building. Chris Dodd supporters had, it seemed, severely miscalculated by not eating all day.

The meeting started when Larry Staunton, a professor of physics and astronomy and hence the only person capable of caucus math, went over all the procedures. The packed room immediately motioned to eliminate candidate speeches, voting over platforms, reading letters from the governor, and electing, among other party positions, members for the "the committee on committees." A tear welled in my eye as I realized how beautiful democracy can be. Then they passed around an envelope to stuff cash in for the party, and my eyes dried right up.

The tallying was especially quick, partly due to the fact that Kucinich and Gravel had no supporters present, and Dodd's two people looked at each other — and the obvious lack of brownies — and split before the voting started. This was not good for Tom Flexner, who, while not actually an Iowan and unable to vote, had flown in from New York and was permitted to organize this precinct. He was a friend of the Connecticut Senator, who he met while, "playing golf with Bill Clinton in Martha's Vineyard." It is shocking that the Dodd message didn't click in Iowa.

Obama crushed the first vote, not only in raw numbers, but in pure awesomeness. Margie and her supporters clapped and chanted and jumped around in their beads. Meanwhile, when the Obama supporters started to chant "Fired up! Ready to go!" into an MSNBC camera, David Gobberdiel, the assistant precinct captain of the far nerdier Clinton crew sighed, smiled and said, "Too much fun."

With the Biden, Richardson and Uncommitted groups up for grabs, the real politicking began. This consisted mostly of individual pleas to "Come on. Really, come on." After 10 minutes everyone decided that they had enough and professor Larry asked people to count again. Of the five delegates allotted, three went to Obama, one to Clinton and one to Edwards. It was over in an hour and a half, which is a lot of time just to vote but a mere blip when you've practiced chanting, clapping and yelling into a TV camera for nine months.

Which is why I was shocked to walk down to the gym and find the Republicans still sitting in their neat rows of folded chairs, waiting for their ballots to be counted while voting, by a show of hands, on their party platform. I'm sure they had their reasons, but I didn't immediately comprehend the logic of following a secret ballot with a process that involved raising your hands in a crowded room to declare your feelings on abortion, gay marriage and immigration.

At 8:30, after Romney had conceded, they were still counting votes. Looking at them slowly raise their hands and ask questions to clarify the very clear rules, I understood why Republicans plans to shrink government never seem to work.