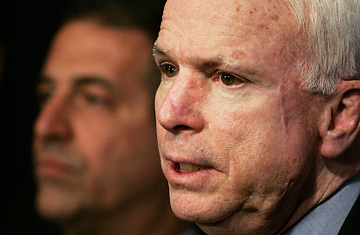

U.S. Sen. John McCain, a Republican from Arizona, speaks to reporters while Sen. Russell Feingold, a Democrat from Wisconsin, listens.

On the same day that the Supreme Court imposed a new limit on students' free speech in the Bong Hits 4 Jesus decision, the Justices ruled the opposite way in another First Amendment case, protecting the rights of corporations and unions to shell out money for political ads shortly before an election.

That may sound sweeping, but it's hard to know exactly what to make of the 5 to 4 decision, with the majority opinion also written, as in the Bong Hits case, by Chief Justice John Roberts. It seems to put a significant chink in the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law, and advocates for limiting campaign spending say it will draw a flood of corporate cash to TV spots pushing one candidate or another. But the decision is also very narrow, meaning it may well preserve the overall impact of McCain-Feingold and doesn't necessarily justify predictions of the end to spending restraint. As with the Bong Hits case, it also starts to show the ideological limits of the Roberts Court, where the President's two appointees, Roberts and Samuel Alito, are less open to sweeping legal change than their counterparts on the right, Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas.

Although it will serve as precedent in similar situations, the campaign finance decision applies only to three TV ads that Wisconsin Right to Life Inc. wanted to run in 2004 opposing filibusters of President George W. Bush's judicial nominees. The ads named Wisconsin's two Senators and urged viewers to contact them about the issue. One Senator, Democrat Russ Feingold, was up for reelection. Since the McCain-Feingold law bans corporations and unions from spending their money (as opposed to money from a separate political action committee) on ads that name candidates 30 days before a primary or 60 days before a general election, Wisconsin Right to Life figured it had a problem.

It need not have worried.

Joined by Justice Samuel Alito, Roberts says the organization's ads could reasonably be seen as opposing the practice of filibustering, rather than the candidacy of Feingold, so they therefore past constitutional muster. (Wisconsin Right to Life won't use the old ads, obviously, but at least now it knows what it can say in new ones.) It's only when an ad is "susceptible of no reasonable interpretation other than as an appeal to vote for or against a specific candidate" that McCain-Feingold kicks in, Roberts says.

This "no reasonable interpretation" standard will apply to all corporations and unions trying to figure out what ads they can pay for, and it's a lot tougher than what most people thought was the old standard: If it looks like an ad for a candidate, then it probably is. That standard grew out of the court's 2003 decision upholding McCain-Feingold's ban on candidate ads just before an election, so long as companies could still spend money on ads about issues.

Things could have turned out a lot worse for friends of McCain-Feingold, because three justices — Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and Anthony Kennedy — wanted to go farther than Roberts and Alito by reversing the 2003 decision and striking down all the statutes restrictions on ads, including the ban on ads advocating a specific candidate shortly before an election.

That brings up an important point. As the court's term draws to a close, it becomes increasingly clear that Roberts and Alito — Bush's two selections for the court — are far different from Scalia and Thomas. As Cass Sunstein, the constitutional law professor at the University of Chicago, describes them, Scalia and Thomas are "visionaries:" justices with a clear view of the Constitution's meaning and an equally clear sense of how they want the law to change. They write or join dissenting or concurring opinions — like the one in this case, or the one that calls for reversing Roe v. Wade in April's decision upholding the federal partial birth abortion ban, or the one by Thomas that opposes free-speech rights for students in the Bong Hits 4 Jesus case — and all of them advocate a fundamental shift to the right in constitutional law, even when it means overturning precedent.

Though Alito and Roberts have often voted with Scalia and Thomas, they are not visionaries. Instead, they pay close attention to precedent, and they write opinions with deep attention to detail and legal craft. Unlike Scalia and Thomas, "they don't thunder," says Sunstein. "Theyre excellent, but not inspiring."

This hasn't meant much in practice this term, but it may have a big effect in the future. It could mean the cornerstones of constitutional law — the limits on presidential power and the precedents like Roe v. Wade — may survive the Roberts court, as Scalia and Thomas continue to thunder on the right while Roberts and Alito exercise the same relative restraint they have shown so far.