(4 of 5)

No one really disputes Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce, and it's silly to argue that health care — which accounts for 17% of the U.S. economy — doesn't involve interstate commerce. Your doctor's stethoscope was made in one state and was shipped to and sold in another. What conservatives mostly argue is that the individual mandate in the bill is unconstitutional and that the government can't regulate something you don't do. Supporters of Obamacare note that it's not a mandate but, in effect, a tax, imposed on people who do not buy health insurance. And that it's not universal; people who are on Medicare and Medicaid, for example, don't need that coverage.

One would like to think that the decision to buy health insurance — or not — is a private one. If you're young and healthy, you might just say, I'd rather spend my money on something else. That's your right — and it may well be a rational decision. But it's hard to argue that not buying health insurance has no interstate economic consequences. Opponents say Congress can regulate commercial activity only, and not buying health insurance is not an activity — it's doing nothing.

But what happens when that healthy, young uninsured woman goes skiing and tears her anterior cruciate ligament and has to have emergency surgery? She can't afford to pay the full fee, and the hospital absorbs much of the cost. That's basically a tax on everyone who does have health insurance, and it ultimately raises the cost of hospital care and insurance premiums. I devoutly believe in Justice Louis Brandeis' famous dissent in the 1928 wiretapping case of Olmstead v. United States, in which he wrote that the Constitution conferred on all of us "the right to be let alone — the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men." Amen. But doing nothing can be a private decision with public consequences. Some argue that the Affordable Care Act is cynical. As a University of Pennsylvania Law Review article contended, "Making healthy young adults pay billions of dollars in premiums into the national health-care market is the only way to fund universal coverage without raising substantial new taxes." But cynicism — or pragmatism — is not proscribed by the Constitution. The Affordable Care Act may be bad legislation, as some contend, but that doesn't mean it's unconstitutional. There's no law against bad laws. The remedy for bad laws is elections.

IV. Immigration

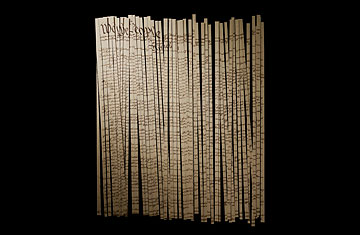

'All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.'

14th Amendment, 1868

All around the world, there are basically three ways of acquiring citizenship: by birth, by blood or by naturalization. All of them depend on the circumstances of one's birth. The principle of jus soli (right of the soil) means that if you're born within the borders of a country, you're automatically a citizen. Jus sanguinis (right of blood) means that if your parents are citizens of a country, you too are a citizen, no matter where you were born. And naturalization is the process by which a noncitizen becomes a citizen through residency, a test or an oath — or some combination of the three.

The U.S. is one of the last nations — and by far the largest — to follow the principle of jus soli, better known as birthright citizenship. The 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, basically holds that if you're physically born in the U.S. or a U.S. territory, you're a citizen. Full stop. Of the world's advanced economies, only the U.S. and Canada offer birthright citizenship. No European nation does so. Nor does China or Japan. We are in part a jus sanguinis nation as well in that children of American citizens who are born outside the U.S. can become citizens. But in the latter case, it's not so simple. For example, an out-of-wedlock child born to an unemployed illegal-immigrant mother in Paris, Texas, is a citizen when he breathes his first breath, whereas a child born to an American mother and father working for IBM in Paris, France, must apply for a certificate of citizenship and file months or years of paperwork with the State Department to show evidence that the child qualifies for American citizenship. Last year nearly 620,000 immigrants went through the naturalization process in the U.S., which on top of the paperwork includes tests in English and civics that many jus soli citizens might not be able to pass.

It was the 14th Amendment — one of the post–Civil War Reconstruction amendments — that made it crystal clear that anyone born in the U.S. was a citizen. It was passed for a very specific reason: to establish that former slaves were indeed citizens and entitled to all the rights of citizenship, including voting. For African Americans, this was a new birth of freedom. The 14th Amendment was a reaction to the infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857, which asserted that African Americans were "beings of an inferior order" who "had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." That ruling declared that African Americans could never be U.S. citizens and were therefore not entitled to any constitutional protections. The 14th Amendment reversed that. In drafting the 14th Amendment, Congress was definitely not thinking about illegal immigration. At the time, the country needed a lot more immigrants, legal or otherwise. Congress was thinking more practically. It wanted to emancipate blacks and allow them to vote so that white Southern Democrats would not try to reverse the gains of the Civil War. It was also a direct response to the Black Codes passed by Southern states that sought to put freed slaves into something like the condition they were in before the war.