(2 of 5)

It is true that the framers, like Tea Partyers, feared concentrated central power more than disorder. They were, after all, revolutionaries. To them, an all-powerful state was a greater threat to liberty than discord and turbulence. Jefferson, like many of the antifederalists, did think the Constitution created too much centralized power. Most of all, the framers created a weak Executive because they feared kings. They created checks and balances to neutralize any concentration of power. This often makes for disorderly government, but it does forestall any one branch from having too much influence. The framers weren't afraid of a little messiness. Which is another reason we shouldn't be so delicate about changing the Constitution or reinterpreting it. It was written in a spirit of change and revolution and turbulence. It was not written in stone. Its purpose was to create a government that could unite and lead and govern a new nation, a nation the framers hoped would grow in size and strength in ways they could not imagine. And it did.

Some news events have a way of triggering instantaneous constitutional sparring: the rise of WikiLeaks fueled the debate over the limits to free speech; the shooting of Representative Gabrielle Giffords did the same for the right to bear arms. But a number of other issues in the news at the moment have deep constitutional subcurrents. Let's look at four that are raising constitutional questions: Libya, Obamacare, the debt ceiling and immigration.

I. Libya

'The Congress shall have power ... To declare war.'

Article I, Section 8

'The president shall be commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States.'

Article II, Section 2

May 20 marked the 60th day since President Obama launched military action in Libya. Speaker of the House John Boehner has asserted that the President is in violation of the War Powers Resolution, passed in 1973, which requires the President to withdraw U.S. forces from armed hostilities if Congress has not given its approval within 60 days. The Administration argues that what we're doing in Libya does not meet the threshold of hostilities in the legislation so the resolution does not apply.

Let's be honest. No President wants to have his powers as Commander in Chief curtailed. Presidents basically say, I'm the Commander in Chief, and my duty is to protect and defend the U.S., and I can't be tied down by congressional foot dragging or posturing on C-SPAN. When it comes to presidential Executive power, where you stand is where you sit. And if you're sitting in the Oval Office, presidential power looks pretty good. All Presidents — regardless of party — tend to have expansive views of Executive power. And pretty much every presidential candidate, including then Senator Obama, criticizes the sitting President for overreaching. Candidate Obama supported the War Powers Resolution. In 2007 he said, "The President does not have power under the Constitution to unilaterally authorize a military attack in a situation that does not involve stopping an actual or imminent threat to the nation." When it comes to being Commander in Chief, Presidents have a lot more in common with one another than with whatever their own party says when it is out of power.

Since the signing of the Constitution in 1787, Congress has declared war exactly five times: the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Spanish-American War and World Wars I and II. And since 1787, Presidents have put U.S. military forces into action hundreds of times without congressional authorization. The most intense of these actions was the Korean War, to which President Truman sent some 1.8 million soldiers, sailors and airmen over a period of just three years, and 36,000 lost their lives — but he never sought or received a congressional declaration of war. Congress has not declared war since World War II, despite there being dozens of conflicts since then.

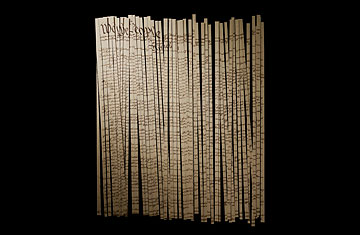

The War Powers Resolution was meant to counteract what Nixon, and Johnson before him, had done in Vietnam. Congress felt manipulated and deceived and wanted to affirm its power as the war-declaring body. But the law is not exactly a macho assertion of congressional prerogative — it politely asks for an authorization letter and then gives the President a three-month deadline. Yet since 1973, Presidents have at best paid lip service to the resolution. Presidents of both parties have used military force without prior approval from Congress — for example, in Libya in 1986, in Panama in 1989, in Somalia in 1992, in Bosnia in 1995 and in Kosovo in 1999. But in an age of potential nuclear war, global terrorism and missiles that can be launched in seconds and take only minutes to travel thousands of miles, the President must be able to act quickly. In 1787 it took months to order uniforms and muster troops — and declarations of war were written on parchment with quill pens.

It seems clear that when it comes to Libya, Obama did not adhere to the spirit of the War Powers Resolution. He did not ask for authorization, even though he would probably have had congressional support back in March. The White House argues that the operations "do not involve sustained fighting or active exchanges of fire with hostile forces, nor do they involve U.S. ground troops." In short, the Administration is saying, You call this a war? We're not even the lead dog.

The question is, Do Americans really want to let Congress have the sole power to commit U.S. forces to action? The law permits the President to act unilaterally, at least for the first 60 to 90 days. But Congress is trying to have it both ways: it wants to reassert its primacy, but it's not sure whether it really wants to end the action in Libya. If it did, lawmakers have one very clear power that could stop the action overnight: they can defund it.