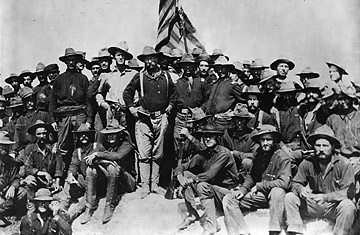

Theodore Roosevelt, center left, with his Rough Riders on San Juan Hill during the Spanish-American War

With tactical commands located on all of earth's continents, the U.S. military is the world's sole colossus. But ambivalence to the use of American power has always run deep within the U.S. In How We Fight: Crusades, Quagmires, and the American Way of War, Dominic Tierney, an assistant professor of political science at Swarthmore College, outlines what he sees as two parallel modes in the American experience of war that have lingered since the Civil War. TIME spoke to Tierney about recent American crusades and quagmires and how different it all was for the nation's founders.

It seems that zeal has been central to much of this nation's feelings behind war. You call Americans the most ideological people in the world. That must sound like news to most Americans.

There's a profound national ideology, which is this belief in democracy and freedom and self-determination and limited government. It's basically a consensus belief; Americans don't see themselves as ideological because everyone believes in this ideology. What's interesting is that Americans are far more ideological than Soviet communists or, say, Chinese communists were. At the end of the Cold War, those countries just discarded their communism. But it would be impossible for Americans to discard their belief in the American way so easily.

How did you decide upon this dichotomy of crusades and quagmires?

If you look at the wars in American history, from the Civil War to the World Wars to Iraq, they all seem quite unique. But there are actually some important patterns about how we experience war, how we think about war. These conflicts don't repeat themselves, but they do rhyme. Basically, for the past 150 years we've liked smashing tyrants, but we've hated dealing with the messy consequences. And so what we see in U.S. history is that wars against enemy countries [including the Confederacy] are seen as crusades for grand majestic objectives like regime change. But nation-building missions where we try to stabilize a conquered land — we tend to see these as quagmires, as disastrous failures.

And these are themes that are consistent throughout? The face of American might in the 1860s looked very different from how it does today.

America's power position has changed dramatically in the last century and a half. It's gone from a rising power to one of several great powers to one of two to the only great power. And soon it may gain company again with China and India. America's power allows America to launch these crusades — if it was weaker, it would launch fewer — but I'd also say that this pattern has existed for 150 years, when the US was far weaker.

And, of course, technology has changed: the Civil War involves campaigns of stockades and muskets and you look at war today with daisy-cutter bombs and weaponized anthrax and Predator drones. That said, the patterns I talk about tend to hold true even in these profoundly different environments. It hasn't changed the basic American response.

In making your argument about the nature of this response, you invoke George Kennan, the diplomat who authored the U.S.'s containment strategy during the Cold War. He saw the U.S. war machine as some sort of primeval beast.

Kennan, back in the 1950s, felt the U.S. was like a "prehistoric dinosaur." It was slow to spot threats, it would just sit there while threats built up, until at some point it got attacked. Then it would lurch around its environment like a crazed dinosaur, basically destroying its environment. What he calls a raging dinosaur, I may call a zealous crusader.

Your chapter on the Spanish-American War provides a handy illustration how crusader efforts get remembered and quagmires are often forgotten. We all know about Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders in Cuba, but few remember or talk about the U.S. annexation of the Philippines.

In 1898, we went to war against Spain and the war was all about Cuba. But by the end of the war, the goals had escalated dramatically and we had conquered the Philippines. This was 7,000 islands, 7,000 miles away, and this led to one of America's first nation-building missions, which began as a very bloody counterinsurgency war against Filipino nationalists. There are some very interesting parallels between this war and the war in Iraq. Similar number of Americans dead, about 4,000, as well as accusations of U.S. torture and mistreatment of captives.

The American public very quickly grew weary of the operation. It was engaged in this counterinsurgency that Americans couldn't understand, so far removed from the glorious Spanish-American War — just in the same way counterinsurgency in Iraq was so far removed from the glorious toppling of Saddam. Even the champions of annexing the Philippines, like Theodore Roosevelt, grew disillusioned. He described it as our "heel of Achilles." But we stayed in the Philippines until 1946, and it was a very significant nation-building operation, with some failures and some successes.

You point to the way the founding fathers thought about the military as a kind of antidote to how the U.S. has waged war since the Civil War. Why?

The founding fathers and their initial successors held the opposite view of war to modern Americans. They didn't see wars as crusades; they saw wars as those fought for limited goals — say, against Britain in 1812 and Mexico in 1846. In fact, the founders believed that going on grand crusades could imperil the American project and would be very dangerous. Some were even opposed to having a standing army.

Meanwhile, interestingly, the founders weren't as averse to nation-building as later Americans would be. The early military was building roads, schools and national infrastructure, surveying and mapping the west, giving out humanitarian aid to settlers. And a lot of these broader-type activities — along with others we should celebrate less, like the treatment of Native Americans — went way beyond simply smiting enemy tyrants. While the context is worlds away from today, there's some interesting points of analogy. If the founders built a multipurpose army designed for a wide range of challenges, I think we need our own multipurpose army for our own very different challenges today.

So should the U.S. military don blue helmets and be peacekeepers? Or should it learn to curb its crusader zeal?

The irony of course is that regime change leads directly to nation-building. We need to be more careful about overthrowing tyrants. The flip side of the story is that we need to think about our aversion to nation-building. Think about the Iraq war with Bush and Donald Rumsfeld — they were archcrusaders who wanted to overthrow the Taliban and then get out, overthrow Saddam Hussein and then get out. You throw them out and don't have a plan for what happens next. That's the worst of all worlds.