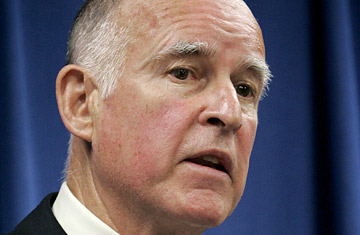

California Attorney General Jerry Brown will work to void the state's gay marriage ban.

Attorneys-General of California are usually expected to defend successful statewide propositions against those who would challenge their legality in court. But Proposition 8, which ended gay marriage in the state, passed while the Attorney-General's office happens to be occupied by Jerry Brown, the celebrity activist, former two-term governor and mayor of Oakland, a man for whom political second a cts are second-nature. Early on, Brown had indicated he would fulfill his duties as A.G. and use the powers of his office to defend Prop 8. Indeed, Brown had sided with opponents of gay marriage earlier this year when the state Supreme Court ruled on whether a previous ballot initiative banning gay marriage was legal. As foot soldiers and generals alike on both sides of the war over gay marriage prepared to battle in court, Brown told TIME an evolving understanding of what was at stake prompted him to turn things around.

With an 111-page legal brief that has surprised legal scholars, Brown reversed course and repudiated his previous statements indicating he'd likely support the legality of Prop 8. Instead, on Friday, he urged the state's Supreme Court to overturn the vote, a move that would infuriate conservatives who are still white-hot mad over the court's historic 4-3 decision that earlier this year prohibited all forms of discrimination against gays, and mandated the state issue marriage licenses to gay couples. In a wide-ranging interview, Brown told TIME that his view of the legal merits of the case had evolved over the past several weeks, and explained why he now thinks the right to gay marriage in California is as fundamental as such bedrock principles as the right to property and to liberty itself.

"Right from the beginning, it looked like the only question was whether the vote was an amendment to the state constitution or something more, a revision," Brown told TIME, explaining his original stance in favor of Prop 8's legality. "But the precedents for saying that the vote was a revision were very few. Based on that, I didn't think we could call it a revision, and therefore Prop 8 looked valid."

But as his staff of more than 30 lawyers began researching the case, Brown said a few urged him to look at the question from a much broader perspective. "Some of the staff said 'wait a minute, there is another way of looking at this.' The idea was that gay marriage involves a basic liberty interest, rights that formed a foundation for our Constitution, that we enjoyed even before California became a state. That was a new way to look at this." Rights like that, he came to believe, can't be taken away, at least not by something as simple as constitutional amendment by popular vote. Instead, those rights he said, are "inalienable" in the same sense that the Declaration of Independence speaks of inalienable rights.

"The issues raised here go far beyond the issue of same-sex marriage," Brown wrote in his brief. "The question is whether rights secured under the state Constitution's safeguard of liberty as an 'inalienable' right may intentionally be withdrawn from a class of persons by an initiative... This litigation, perhaps for the first time, poses a more fundamental question: Is the initiative-amendment power wholly unfettered by the California's Constitution's protection of the People's fundamental right to life, liberty and privacy?" In other words, aren't some rights so sacred that they can't be taken away?

On Friday, Brown's legal brief ignited a statewide debate among legal scholars, with discussion of the argument dominating law professor list-servs and e-mail lists. "It's creative and contains thoughtful insights," says Vikram Amar, a constitutional law professor and dean of academics at the University of California-Davis. "It profoundly highlights the almost paradoxical character of American constitutionalism: That minority rights exists only to the extent that the majority stands behind them."

Amar, who has taught at all four law schools in the University of California system, says America has always struggled with the seemingly conflicting ideas about the sanctity of basic rights like those in the Bill of Rights and ability of the majority to take them away. "It strikes us as strange the notion that minorities should have to depend on a majority to confer something we think of as a right," Amar says. "But the idea of popular sovereignty, which is another way of saying majority rule, means just that. We can make sure that majorities are reflective, deliberative and that they consider what they are doing before they are doing it — but at the end of the day, majorities can change the rules in ways that screw over the minorities. We may not like it, but we generally acknowledge that as lawful."

Amar told TIME that Brown's argument seeks to set barriers around those basic liberties in California — even against popular referendums. But Amar said it remains to be seen how many, if any, of the seven justices see things his way. Yet Brown's brief will be taken seriously, he said, and will undoubtedly influence the opinion once the closely divided court rules. "It certainly helps gay marriage supporters," he added.

When the California Supreme Court issued its decision legalizing gay marriage in May, it declared that ""The very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of the majorities and officials and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts." Brown has apparently now taken that as a touchstone, arguing that some rights cannot be taken away by the majority, absent special circumstances. "The Declaration of rights in Article I gives certain rights a privileged status," Brown told TIME. "Those rights, including the right to marry, are in a unique position. And while we cite no precise precedent saying so, our argument does follow from that position, and from the logic of the marriage case itself."

What would it take to take away such an "inalienable right"? Brown said that's up for the Courts to decide, but it would probably take something more like what is required to amend the U.S. Constitution, a three-fourths vote, for instance. "There has to be a special burden imposed on an effort to take away these rights," he said. "Prop 22 [the previous initiative banning gay marriage] passed with 61% of the vote, and yet the Supreme Court said it was invalid. You can't just come back with [November's] 52-48 vote and write the same language of that proposition into the constitution and call it an amendment." The California Supreme Court is expected to hear arguments by March and issue a ruling later this year.

Brown said reaction to his position has been mixed, with supporters of gay marriage obviously cheering. Others, he said, have been less excited. But after more than four decades of public life, and no plans to quit anytime soon, Brown seemed to relish the historic significant of the case. "Isn't this what the Federalist Papers were all about? What Madison was after?" Brown told TIME. "These questions go back to the beginning, back to Justice Marshall and the question of judicial review, to Marbury v. Madison. This is a topic of constant constitutional inquiry: What is the role of the court, and what is the role of the people? We have a unique system, and these questions have always been controversial." Oh yes, Brown also told TIME that he is exploring the possibility of seeking a third term as governor once Arnold Schwarzenegger's ends in 2010. Some habits are hard to break.