(2 of 3)

After Michael Dukakis and George H.W. Bush traded passive-aggressive jabs in 1988, O'Connor simply didn't invite the presidential candidates in either 1992 or 1996. The slight was particularly painful for Bill Clinton, who developed an affinity for the Catholic Church as an undergraduate at Georgetown University. And it was compounded by the fact that in 1992, O'Connor invited Pennsylvania Governor Robert Casey to be the featured speaker. The pro-life Catholic Democrat had himself been denied a speaking slot at that summer's Democratic National Convention and the dinner arrangements were seen as payback.

A truce seemed in sight in 2000 when O'Connor was succeeded by Cardinal Edward Egan, a prelate far less interested in making political waves. And indeed he invited Al Gore and George W. Bush to the event that fall. Just four years later, though, both Bush and John Kerry were left off the list. "The issues in this year's campaign," explained an archdiocesan spokesman then, "could provoke division and disagreement." Critics speculated that church leaders were more concerned about keeping Kerry, a pro-choice Roman Catholic, off the stage.

Why then was Obama welcomed to the Al Smith Dinner, his hand on Cardinal Egan's shoulder as they chuckled together, while Kerry had to stay away? It helps that Obama is not Catholic. Some Catholics have criticized his support for abortion rights, but as he is not a member of their tradition, they don't feel the same need to sanction him. But more importantly, the political landscape for Catholics has changed since 2004.

In a hierarchical tradition like Catholicism, debates don't happen very often. Right now, however, American Catholics are going through a revival of the arguments that took place in the 1980s between bishops who believed abortion ought to be the top political and moral focus of the church and the camp led by the late Cardinal Joseph Bernardin that argued for a more "consistent ethic of life."

In early October, Bishop Joseph Martino of Scranton released a letter to be read in every pulpit in the diocese that said, in part: "Abortion is the issue this year and every year in every campaign. [Catholics] are wrong when they assert that abortion is only one of a multitude of issues of equal importance. Abortion must take precedence over every other issue." But just last fall, the American bishops released Faithful Citizenship: A Call to Political Responsibility, a document that reminded Catholics that "all life issues are connected." Over the past few years, archbishops around the country have spoken out in favor of immigration reform, opposing the use of torture, and advocating policies that focus more on the poor.

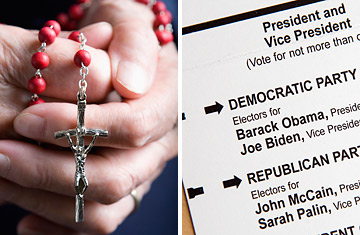

As a result, many Catholics can now argue that neither party fits precisely with Catholic social teaching — the Democratic position on abortion is still unacceptable but so are GOP positions on education and health care and the war in Iraq. This realization is reflected in changing party identification — as of this past February, 41% of Catholic voters called themselves Independents, an 11-point increase since 2004. And in opinion polls, Catholics are evenly divided between Obama and McCain.