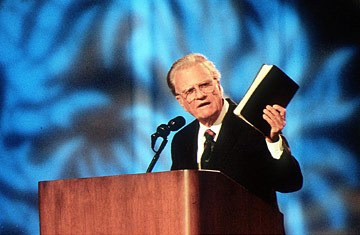

Billy Graham in San Francisco, October 21, 1997.

Christopher Hitchens once devoted an entire book to portraying Mother Teresa as a phony, so perhaps Billy Graham got off easy when Hitchens described him, in a recent C-Span appearance, as "a self-conscious fraud," who didn't believe a word of what he preached, but was just in business for the money.

The celebrated atheist, whose latest polemic, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, is firmly entrenched on the bestseller list, also called Graham a power-worshiping bigot who made a living by "going around spouting lies to young people. What a horrible career. I gather it's soon to be over. I certainly hope so."

Graham, now 88 and in failing health, was recently hospitalized for two weeks for intestinal bleeding.

Over the course of his long public ministry, Graham has certainly acquired his share of critics — a group which includes Graham himself. In our hours of interviews with him — while researching our own book, The Preacher and the Presidents — he was quick to find fault with his own conduct and quite willing to explore the reasons behind the mistakes he admitted making. The odd thing about Hitchens' attack is not that he assaults an ailing icon — that's both his specialty and his right — but that the evidence he cites actually proves him wrong.

Hitchens calls as his main corroborating witness a Canadian contemporary of Graham's, whom he misidentifies as "James Templeton." Hitchens explains that as a young firebrand preacher, Templeton (whose name was actually Charles), found his faith faltering; but when he challenged Graham, Hitchens claims, the evangelist told Templeton that it was too late to stop now — "We're in business" — and proceeded to spend the next 50 years as a kind of religious racketeer.

The true story of Graham's encounter with Templeton is fascinating and critical in understanding the ministry that followed — just not in the way Hitchens describes. Like Graham, Templeton was young and handsome; he was also the more talented preacher. But his growing spiritual questions led him to leave the sawdust trail in 1948 for Princeton Theological Seminary to put himself through a kind of theological boot camp. He tried to talk Graham into coming with him; Graham's unquestioning faith in the literal truth of the Bible, he said, amounted to intellectual suicide. He tried to phrase it in Graham's own terms: "You cannot disobey Christ's great commandment to love God with all thy heart and all thy soul and all thy mind." They continued to debate all year whenever their paths crossed, until finally in the summer of 1949, as Graham was preparing for what would be his breakout crusade in Los Angeles, Templeton confronted him one more time. "Billy, you're 50 years out of date," he said. "People no longer accept the Bible as being inspired the way you do. Your faith is too simple ... You're going to have to learn the new jargon if you're going to be successful in your ministry."

Templeton was actually pressing Graham to modernize his ministry, make it more commercially viable. What could be more tempting — to a rising preacher trying to reach young people, a preacher who stressed being approachable and relevant — than to tailor his theology to the tastes of the times, especially if the latest scholarship allowed wider appeal? But for Graham this was not an option. He felt that he could either believe the Bible or leave the ministry. "It was not too late to be a dairy farmer," he concluded.

In the end, as the story was told many times over the years, Graham says he took a walk late at night and prayed. He didn't understand everything in the Bible. But he decided to accept it, and preach it, without apology. In years to come critics like Reinhold Niebuhr would challenge his preaching as too simple, too far removed from the complexity of the human condition. But not even Niebuhr questioned the sincerity of Graham's faith or motives. And neither, contrary to Hitchens, did Templeton. "I disagree with him profoundly on his view of Christianity and think that much of what he says in the pulpit is puerile nonsense," Templeton wrote in his memoirs. "But there is no feigning in him: he believes what he believes with an invincible innocence. He is the only mass evangelist I would trust. And I miss him."

The charge that Graham went into ministry to get rich is just as easily refuted, both by what he did and didn't do. Well aware of how easily a famous preacher could be destroyed by financial or sexual scandal, Graham took pains early on to protect himself from both. He insisted that crusade accounts be audited and published in the local papers when the crusade was finished. Having founded the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association in 1950, he took a straight salary, comparable to that of a senior minister of a major urban pulpit, no matter how much in money his meetings brought in. He was turning down million-dollar television and Hollywood offers half a century ago. He never built the Church of Billy Graham, and while he lived comfortably, his house is a modest place. If he had wanted to get rich, he could have been many, many times over.

Hitchens is on more solid ground when he attacks Graham for his comments about Jews in a 1972 Oval Office meeting with Richard Nixon. That conversation was indeed vile, and since it was disclosed in 2002, Graham has apologized repeatedly for his part in it. "I cannot imagine what caused me to make those comments, which I totally repudiate," he said. "Whatever the reason, I was wrong for not disagreeing with the President ... I don't ever recall having those feelings about any group, especially the Jews, and I certainly do not have them now." When we asked Graham about the conversation, his shame was obvious, and he confessed to the other fault at work that day — his sycophancy, the courtier's habit of trying to win favor with the king by embracing even his most odious ideas. "I think I was just trying to agree with what he said or something," Graham told us. Hitchens may reject Graham's many apologies if he chooses, and discount his remorse more evidence of fraud. But rational people should have a hard time accepting Hitchens' characterization of Graham as "a disgustingly evil man."

Gibbs and Duffy's book, The Preacher and the Presidents, was published in August.