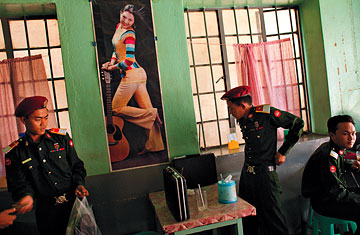

Ruling class Army cadets at ease in a juice bar in Pyin U Lwin, home to top military academies for training officers

(2 of 3)

Certainly, the revenues from natural gas, oil, timber, gems and other commodities haven't been used for the betterment of the Burmese. Five years ago, the country's military rulers spent billions of dollars building a sprawling new capital out of scrubland, forcing many civil servants to move from Rangoon with just a couple of days' notice. In two decades, the nation has doubled the number of soldiers in the Tatmadaw, as the Burmese armed forces is called, even though there are far fewer battles to fight against ethnic insurgent groups. Twenty Russian fighter jets — not to mention suspicious nuclear technology — are the military's latest playthings. On the outskirts of Pyin U Lwin, another costly megaproject is materializing: a cybercity whose vastness belies the fact that Burma, even with a proliferation of Internet cafés in Rangoon, remains one of the least wired nations on earth. And in the big cities and beyond, construction crews are busy outfitting Burma's upper classes with marble-lined mansions, fancy vacation homes and towering Buddhist pagodas chiseled with the names of generals and their cronies.

The building boom has surged even as at least one-third of the nation lives below the poverty line, according to the U.N. Inflation is so high that the U.N. estimates an average household spends 73% of its income on food. The World Health Organization ranks the country's health care system as the second worst in the world, just ahead of Sierra Leone's. On the recently built highway from Rangoon to Naypyidaw, the new capital, I meet a 15-year-old girl who spends her days in the 45C heat carrying chunks of rock on her head. She has been working on this road since she was 11 years old. Her daily pay? $1.50 — and that's when Max Myanmar, a company run by a junta crony whose name was added to the U.S. sanctions list last year, bothers to pay at all. On its polished English-language website, Max Myanmar says employees' welfare is a top priority and that the conglomerate covers "field allowance, bonus, meals, medicare, education allowance and annual celebrations for pleasure and relaxation." The girl laborer has enjoyed none of these. But she dreams one day of reaching the end of her road. "I have heard that Naypyidaw has so much electricity that nighttime looks like day," she says. "Can you imagine such a beautiful place?"

Following the Money

With the nation set to hold carefully orchestrated elections later this year, the economic disparities may soon yawn even wider. The junta ignored the results of Burma's 1990 polls, which the military's proxy party lost badly to Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (she remains under house arrest). Now, military leaders seem to want to present a fig leaf of civilian rule to the West. Top posts like the presidency and key Cabinet seats, as well as a big chunk of parliament, will be reserved for military members. But to maintain the appearance of a transition to civilian government, the junta has in recent months privatized dozens of state-owned (read: military-owned) companies. Auctioning off these enterprises creates cash to fund the military's proxy Union Solidarity Development Party in the upcoming polls. In addition, many high-ranking officers are being forced to stand in the elections and they, along with other top brass uncertain about the postelection landscape, must be worried about losing their military lifeline. A redistribution of state assets to people close to them secures their future.

Indeed, control of factories and banks, gas stations and ruby mines has been handed over, without exception, to a select circle of favored businessmen or military progeny. Many of these men — for they are all men — are targets of Western sanctions, such as Tay Za, a DSA dropout whose business empire has tentacles in everything from airlines to hotels, and Steven Law, the son of a drug lord whose conglomerate constructs dams, roads and practically any other project that uses copious amounts of cement. These cronies burnish ties with the junta through directorships, donations and even marriages. "I don't know of a single big company that doesn't have a princeling or other [general's] family member on its board or involved somehow," says economist Turnell. "The problem with this system is that these robber barons aren't creating an environment for sustained growth or the building of industry. It's just pure racketeering."

I see how wealthy the Burmese elite has become when I tour the Mindhama Residences in Rangoon, a Tay Za – owned housing development just across the street from an exhibition center where massive slabs of jade are piled high on government trucks. With villa types named after Burma's mineral wealth, like Imperial Jade and Red Ruby, the mansions start at $850,000 and go up to $1.2 million, not counting interior decor. All but one has been sold — this in a nation where per capita GDP is just $442, according to the IMF. Might I be interested in the remaining one? The agent allows me to gawp at the splendor: swirls of gilt and meters of marble, Jacuzzi bathtubs, crystal chandeliers. I feel like I have wandered into a Texas McMansion. "Who has bought the other houses," I ask, feigning interest in my potential neighbors. "Some businessmen," he says. "But mostly ..." he trails off, then taps his fingers to his shoulders, the Burmese code for army stripes.