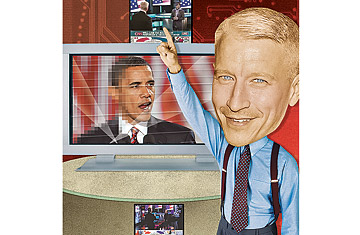

On election night, the networks spent a valiant couple of hours attempting to avoid reporting the news. That news, after they had called Ohio for Barack Obama around 9:20 p.m. E.T., cutting off any path to victory for John McCain, was that the election was over and Obama was the next President of the United States. But until 11:00:01 p.m. E.T., the press discussed how Obama might govern if he won, without directly saying that, oh, right--he had.

There was a practical and ethical reason for journalists' shyness. The West Coast had not yet finished voting, and the TV networks have...