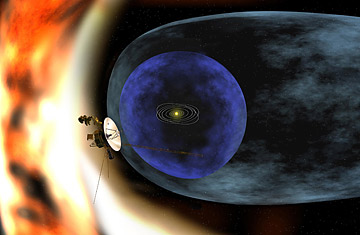

An artist's rendering of the Voyager probe on the outer limits of the heliosphere

Dissing NASA has never been easier. The space shuttles were — how to put this charitably? — imperfect vehicles. The space station is a gorgeous, $100 billion machine that has been hard at work since 1998 doing, um, something or other. As for NASA's next generation of manned rockets? Don't look now, but the launchpads are bare.

But there's more to NASA than its dreary and drifting manned program. There are the robots too. Last week's launch of the SUV-sized Mars Curiosity rover generated plenty of well-deserved coverage, as did reports of the progress the 34-year-old Voyager 1 and 2 probes are making in their quest to become the first spacecraft to leave the solar system.

Left unmentioned, however, was that Curiosity and the Voyagers are by no means the only chicks in the NASA flock out there exploring. Indeed, interplanetary space is more populated than ever by American machines. Mercury, the moon, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and Pluto are all being studied up close by NASA probes or are about to be — a government-funded winning streak that's easy to forget in an era in which bashing Washington and dismissing science are too often the political order of the day.

NASA's hot hand in the unmanned space game can be traced back to the summer of 1997 when the Sojourner rover landed on Mars. The pint-sized machine was no bigger than a microwave oven, but the pictures it beamed back were dazzling and the mere fact that the thing could move — tire tracks in the Martian soil! — captivated space watchers.

But Pathfinder's success had deeper roots — stretching back to the first days of the tenure of NASA administrator Daniel Goldin, who ran the agency from 1992 to 2001. Goldin declared an end to the days of the Cadillac space probes — unmanned ships costing $1 billion each and typically launched in pairs in case one of them failed — and instructed engineers to build their spacecraft for a few hundred million each and to use off-the-shelf parts whenever possible. "Better, faster, cheaper" is how he labeled the new ethos — a slogan that grumbling engineers quickly lampooned as "Better, faster, cheaper: pick two."

Two failures of Mars probes, in 1998 and 1999, seemed to vindicate the skeptics, but NASA quickly found its footing, and two orbiters, one stationary lander and two more rovers have all followed successfully. That multiship program is about more than just putting points on the board. The various Mars ships often work in tandem, with the orbiters helping to relay signals back from the landers, as well as scouting out new sites for other ships still to come. Curiosity, for example, is bound for the Gale Crater, a massive formation in Mars' eastern hemisphere that orbital reconnaissance has shown was once deluged with water. That's exactly the kind of place you want to go when you're looking for signs of extinct — or even extant — life.

Mercury has not gotten nearly as much attention as Mars, but the innermost planet will take what it can get, having been largely ignored since the Mariner 10 spacecraft made three flybys in 1974. The Messenger probe, launched in 2004, was designed to make up for that. The ship executed three flybys of its own in 2008 and 2009, and in 2011 became the first spacecraft ever to orbit the planet. Just two weeks ago, NASA announced that the ship is functioning so well that its prime mission will be extended for a year, to March 2013.

"During the extended mission we will spend more time close to the planet, we'll have a broader range of scientific objectives, and we'll be able to make many more targeted observations," said principal investigator Sean Solomon.

The moon similarly fell off America's radar screen after the Apollo landings were completed and later plans by the George W. Bush Administration to resume manned missions were scrapped by the Obama White House. Nonetheless, robotic studies have continued. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), launched in 2009, is still at work, mapping surface features in a detail not seen even in the glamour days of Apollo. So sharp are the LRO's cameras that the ship was able to beam back images of all six Apollo landing sites — with foot tracks left in the soil four decades ago sill faintly visible.

The GRAIL mission — for Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory — followed the LRO moonward in September. The spacecraft is actually two spacecraft, designed to orbit the moon in tandem, keeping a precise distance between themselves. When the twin ships fly over areas of higher density, the slight increase in gravity will cause the space between them to flutter by as little as the width of a human red-blood cell. Those tiny changes will be all the GRAILs need to assemble a detailed map of the lunar interior.

Deeper in space, the Juno probe, which was launched to Jupiter in August and will arrive in 2016, will continue the work of the fabled Galileo spacecraft, which studied Jupiter and its marble bag of moons from 1995 to 2003. Meantime, the Cassini spacecraft, launched in 1997, continues to slalom through the Saturnian system, studying the planet, its rings and its own litter of moons.

Of all the ships in NASA's active fleet, it is the Pluto probe — dubbed New Horizons — that is the least well-known but perhaps most ambitious. Launched in January 2006 — just months before its target world was demoted from a full planet to a dwarf — New Horizons will not get where it's going until 2015. That seemingly slow trip is not for lack of trying: the ship is moving at blistering speed — a record-setting 36,000 mph (58,000 km/h) — and it has good reason to hurry. So remote is Pluto that as it moves farther from the sun in its elliptical orbit, its atmosphere contracts and freezes. If New Horizons doesn't move fast, Pluto's surface will be completely obscured by the time the ship arrives and flies past — headed, like the Voyagers, for the solar-system exits.

NASA has other missions in its long-term plans — including more Mars probes and perhaps a trip to Jupiter's icy moon Europa. As with all things government-run, the agency cannot be absolutely certain of funding for any of those flights, though projections do call for a dramatic increase in the budget for some robotic missions — from $125 million in fiscal 2011 to $923 million in 2015 — thanks to money freed up by the retirement of the shuttles. No matter what becomes of future missions, however, the fleet that's flying now has already put an indelible human stamp on the solar system. The fact that that stamp was made in America is a reason for unabashed pride.