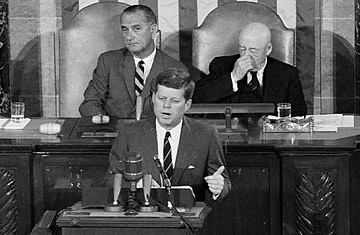

Kennedy before Congress on May 25, 1961

(2 of 2)

According to the new book John F. Kennedy and the Race to the Moon, written by space policy expert John Logsdon of George Washington University and reviewed this week by The New York Times, Kennedy was flat-out desperate to catch up with the Soviets — particularly in the wake of the Bay of Pigs fiasco, which also occurred in April of 1961. Chief adviser Ted Sorensen later described Kennedy as "anguished and fatigued" and "in the most emotional and self-critical state I had ever seen him."

As Logsdon reports it, little brother Bobby Kennedy was sent to crack heads and get the U.S. into the space race pronto. "All you bright fellows. You got the president into this. We've got to do something to show the Russians we are not paper tigers," Bobby is said to have said at one meeting. "If somebody can, just tell me how to catch up. Let's find somebody — anybody. I don't care if it's the janitor over there." The next month, long before the janitor or anyone else had figured out how in the world to fly to the moon, JFK went before Congress and promised to do it.

Even after that, however, Kenndy had his doubts — never mind the unflinching Presidential certainty that figures in so many of the historical retellings of the era. NASA, to its credit, has linked to the transcripts of recorded conversations between Kennedy and then-NASA Administrator James Webb, which were just posted online by the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. The conversations took place in November of 1962, after Americans had at last orbited Earth but well before they were ready for a lunar trip.

"I think this can be an asset, this program," Kennedy confided to Webb. "I think in time, it's like a lot of things, this is mid-journey and therefore everybody says 'what the hell are we making this trip for?' but at the end of the thing they may be glad we made it." However, in the transcript of a later conversation, in September of 1963, Kennedy seemed as if he was asking the same questions the critics were.

Kennedy: Do you think the lunar, the manned landing on the moon is a good idea?

Webb: Yes sir, I do.

Kennedy: Why?

Webb: Because...

Kennedy: Could you do the same with instruments much cheaper?

Webb: No sir, you can't do the same.

Two months after that, on November 21, 1963, Kennedy delivered a speech in which the resolve was back. "This nation has tossed its cap over the wall of space and we have no choice but to follow it," he said. "Whatever the difficulties, they will be overcome." One day after that, he was dead.

There's no telling what would have happened if Kennedy had lived and been reelected — if he would have folded his hand as the manifold crises of the 1960s made space look like an unaffordable indulgence. There's no telling either what would have happened if his assassination hadn't made his moon program an untouchable monument to his presidency — something that Congress and later presidents dared not tamper with until the landing was achieved.

What is clear is that no president since Kennedy has been willing to stake so much of his political capital on so audacious an exploratory goal — and then restate his commitment even when the critics started to howl. As a result, our manned exploration of space has turned into more of a lazy amble — 30 years of the shuttle and perhaps ten more years of the space station, while the moon, which is never more than 252,000 miles (405,000 km) away, seems to grow more and more distant all the time. We don't have to go to the moon. However, as Kennedy said, we can "choose to go to the moon." It's not an easy choice, but it would be a brave one.