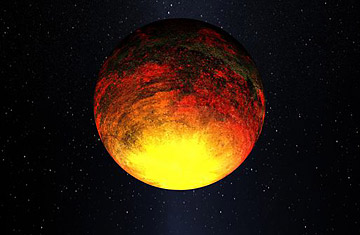

Kepler-10b is a scorched world, orbiting at a distance more than 20 times closer to its star than Mercury is to Earth's sun

For the past two years, NASA's orbiting Kepler telescope has been peering, unblinking, at some 150,000 stars lying just under the wing of the swan in the constellation Cygnus, about 560 light-years away. The probe has been looking for tiny, regular dips in brightness that might signal the presence of a planet passing in front of the star and blocking a fraction of the light.

It's clear they're out there: several so-called exoplanets have revealed their existence to Kepler. None so far, however, has lived up to the ultimate goal of the mission: to find truly Earthlike planets — places small enough and temperate enough to be hospitable to life.

But the planet just announced in Seattle by the Kepler team at the annual American Astronomical Society Meeting is a huge step closer. Called Kepler-10b, it's just 40% larger than Earth — the smallest planet yet found outside our solar system. Not only that: unlike the vast majority of the 500-odd exoplanets found to date, and unlike Jupiter and Neptune, Kepler-10b isn't just a huge ball of gas or ice. Like Earth, it's made of rock. "This is a historic discovery," said Geoff Marcy of the University of California, Berkeley, at a press conference introducing the new planet.

He wasn't really talking about the planet itself, which couldn't possibly harbor life. The main problem is that it's less than 2 million miles (3.2 million km) away from its host star, compared with Earth's 93 million–mile (150 million km) distance from the sun. "The temperature on the sunlit side," said Natalie Batalha of NASA's Ames Research Center in California, who is deputy leader of the Kepler Science Team, "is about 2500°Fahrenheit, which is hotter than lava."

But the fact that it's made of rock, like the only habitable planet we know about — ours — is a huge deal. Astronomers have always assumed that such planets probably do exist, but assumptions aren't always the best idea in a field where the greatest discoveries often come from completely out of left field. They know this one is rocky because they know not only the planet's size, based on how much starlight it blocked, but also its mass. That measurement came not from Kepler but from the ground-based Keck telescope in Hawaii, which measured the minute back-and-forth wobbling of the star as Kepler-10b's gravity tugged on it. (Another planet, called Corot-7b, discovered a year or two ago by a European team, might be rocky as well, but the wobble measurements aren't precise enough to say for sure.)

Combine size and mass, and you've got the planet's density. Kepler-10b's is about 1.6 times greater than Earth's, or about "the density of an iron dumbbell," said Batalha. "That doesn't mean it's actually made of iron — 10b has more powerful gravity, so it squeezes itself tighter than Earth does. But it could certainly have a higher proportion of iron than Earth does."

The other big deal is that Kepler is sensitive enough to have found something this small. On top of that, Kepler's measurements of the star fell within a margin of error of just a few percent. If you want to know exactly how big a planet is, you need to know exactly how big the star is whose light it's blocking. If Kepler can find a planet as small as 10b, it can certainly find one that's smaller. And if it watches long enough, it can find one that's not only the size of Earth but also in a nice temperate orbit — a true twin of Earth.

That won't come for another year or two. In the meantime, though, the Kepler team is getting ready for yet another big announcement just a few weeks from now. The team isn't giving any hints as to what it will be. But given that the satellite has proved it's the world's most powerful planet-finding machine, it will undoubtedly make a few headlines.