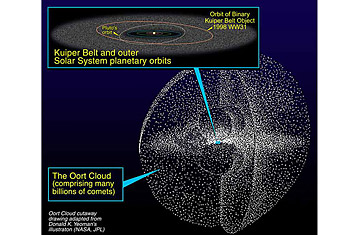

An artists' rendering of the Kuiper Belt and Oort Cloud.

Familiar comets like Halley and Hale-Bopp make a dramatic entrance when they swing in close to the sun, sending million-mile-long streamers of glowing gas across the night sky. But there's a long and twisted backstory behind those moments of glory.

Astronomers have been convinced for decades that the comets were born during the earliest days of the solar system, in the icy darkness around Neptune and beyond. Now, however, there's a new theory, which was just published in the latest issue of Science. Some of our solar system's comets were not in fact born here, the research suggests. Rather, they were kidnapped from another star.

No matter where comets are born, the overwheming majority of them never get their literal moments in the sun the way the ones we know best do. The standard theory explains that after forming in the solar system's furthest and coldest provinces, some comets pretty much stayed there — but many wandered too close to the giant planets Saturn and Jupiter, whose gravity flung them outward to form a huge, spherical cloud of comets, known as the Oort cloud, which surrounds the solar system and reaches halfway to the nearest star. Finally, billions of years later, a nudge from a passing star or a giant cloud of interstellar gas sent an occasional one plunging back toward the Sun, letting the fireworks begin at last.

It's an elegant tale. Unfortunately, says Hal Levison, an astronomer at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), in Boulder, Colorado, it doesn't quite add up. The Oort Cloud is too dim to see directly. Instead, scientists can use the rate at which comets plunge sunward to calculate the cloud's overall population, and the conventional story simply can't build a cloud the size of the one that's out there. It's just too big to have all been birthed by our proto-sun, says Levison, "and not just by a factor of a couple — it's more like a couple of orders of magnitude."

But if the sun could go shopping for its comets elsewhere in the cosmos, there's no way of knowing exactly how big the Oort cloud could could get. That theory actually dates back to the early 1970s, but computer modeling was too primitive back then to test it. Things have changed dramatically, so Levison and his co-authors took another shot at it — and seem to have validated it.

The starting point of their new explanation is the fact that the sun and the rest of the solar system weren't born alone, but instead as part of a litter of perhaps hundreds of stars, packed closely together inside a huge cloud of gas. Under those conditions, comets ejected by Jupiter and Saturn would have been yanked away by the gravity of adjacent stars, then yanked again, so that most of them would have ended up wandering homelessly through the gas cloud. "The stars shared spit," says Levison, who concedes that people at SwRI who wrote up the press release weren't thrilled with this metaphor.

But young stars tend to have powerful solar winds, so before long they would have blown away most of the surrounding gas. And since it was the gas's gravity kept the stars huddled together, its disappearance let the stars and the free-flying comets wander away. Most of the comets would have simply gone off in random directions — and in fact, says Levison, the Milky Way is probably full of such orphan ice balls drifting loose between the stars. But the ones that happened to be heading in the same direction as the Sun would have been captured to form the Oort Cloud.

The way the numbers work out (and assuming this theory holds up) just about every Oort Cloud comet that visits the inner solar system, including Halleys', Hale-Bopp and 2007's biggie, Comet McNaught, formed around a star other than the Sun. At most, says Levison, we're likely to have seen only one locally born comet in the history of human observation. Which means that the next time a visible comet appears in the night sky, it's almost certainly a beautiful immigrant — a cosmic lesson perhaps worth heeding on Earth.

Lemonick is the senior science writer for Climate Central.