Brown fat

It might turn out to be the ultimate irony in our constant battle with the bulge that the best weapon against fat could be fat.

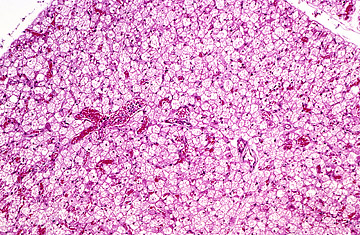

Scientists know that a type of adipose tissue called brown fat tends to burn calories rather than store them. Most adults have far more white fat than brown fat, since it's more important to store calories for future use than to use them up. But when it comes to weight loss, the energy-burning power of brown fat could actually prove useful. And based on continuing research in mice, it appears that researchers have found some promising ways to exploit its fast-acting features.

This week, in a study published in the journal Science, a group of European scientists, led by Stephan Herzig at the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, report that they have discovered a way to make regular white fat act more like the calorie-hungry brown fat and melt away pounds in overweight animals.

The researchers focused on an enzyme known as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), which is involved in a variety of physiologic functions, from regulating blood pressure to controlling inflammation and contracting muscles. (The class of painkillers known as COX-2 inhibitors, like Celebrex, takes advantage of COX-2's role in inflammation by clamping down on the enzyme's activity.)

In mice, boosting the function of COX-2 caused the animals' white fat to act like brown fat, and led to a 20% drop in their weight. "There has been a lot of excitement around brown fat, but ... there wasn't any clear indication that turning up brown fat would make animals lose weight," says Chad Cowan, a professor in the Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard Medical School who studies fat cell development. "What this paper does is make a good link to something that might be clinically beneficial."

In other words, it is the first study to show that manipulating brown fat could make animals thinner, and that gets researchers like Cowan excited about the potential role it may play in regulating weight in humans. Until recently, brown fat has been isolated only in rodents and in newborn human babies; because its primary function is to generate heat, babies need it at birth to help simulate the warmth of the womb, but as they grow and begin regulating their own body temperature, they shed their brown-fat stores. Last year, scientists identified the first evidence of a brown-fat depot in the adults, in the neck, which they hope can be activated to help burn fat.

But what Herzig's team describes is a more efficient way of accessing brown fat — by getting white fat, which is more plentiful in adults — to use up more calories. However, his group showed that it wasn't simply an increase in COX-2 activity that triggered this transformation, and weight loss, but a boost in the enzyme's function in the context of a colder environment.

That caveat is important because the COX-2 enzyme is present in a wide range of body tissues, and revving up its activity may lead to some serious side effects such as clotting problems, increased sensitivity to pain and even muscle abnormalities. Herzig found that manipulating the COX-2 pathway switched white fat to brown fat in the mice only when he simulated cold temperatures through metabolic tweaks — dilating small blood vessels and increasing the pumping of the heart — and made the rodents act as if they were shivering.

Based on his findings, Herzig believes that brown fat may originate from a mother cell of adipose tissue that by default tends to make white fat. But under certain conditions, such as those mimicking a cold environment, these progenitor cells can be induced to make more brown fat. (Two studies last year, including the one describing brown-fat stores in human adults, found that brown-fat cells become more active in the cold.) And while it's not clear how much brown fat would be needed to have an effect on body weight, he suspects that it wouldn't take much. "Based on estimates on animal models, 50 grams of brown fat might be sufficient to increase overall energy consumption in human beings by 20%," he says. "So you would need to activate a relatively little amount of brown fat to substantially impact overall energy metabolism."

That doesn't mean that popping a COX-2 pill will become the next weight-loss treatment du jour. Nor does it mean that COX-2 inhibitors, which repress COX-2 activity, will necessarily lead to weight gain. So far, it appears that activating brown fat requires some very specific triggers, and these results are only the first step in teasing out what those conditions are. But, as Cowan notes, "It's certainly exciting that there may be a way to manipulate white adipose tissue to make it something that is more metabolically active and more brown fat–like."

When it comes to a potentially new treatment for obesity, what better strategy than to utilize something we already have in abundance?