A new study suggests that a simple urine test may one day tell men whether they have prostate cancer that can be ignored or must be aggressively treated.

Currently a man must undergo a series of diagnostic tests, including a surgical biopsy, to confirm that he has prostate cancer. But no test is able to determine reliably whether the cancer is slow-growing and probably nonfatal or aggressive and in need of immediate treatment. (Read "Halting Hormone Therapy Reduces Breast-Cancer Risk Quickly.")

In the Feb. 11 edition of the journal Nature, however, a new study links specific molecules produced by the body to the aggressive form of the disease, suggesting that detecting these molecules could one day to lead to a reliable diagnosis of prostate cancer and a prognosis for patients.

Using new scanning-and-detection technology, scientists looked at more than 1,000 metabolites — naturally occurring products of cell metabolism — and found that about 10 were often present in high levels in samples of blood, tissue and urine taken from patients with aggressive prostate cancer.

"This is proof of principle that we can identify metabolites ... that might be correlated with aggressive prostate cancer vs. slower-growing prostate cancer," Arul Chinnaiyan of the University of Michigan Medical School, who led the study, said in a prepared statement.

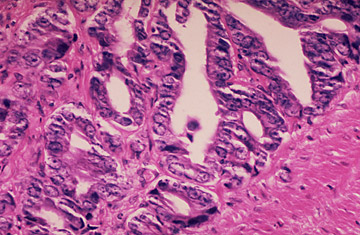

Cancer of the prostate is the most common type among men in the developed world. In the U.S., where 186,000 people receive the diagnosis each year, only skin cancer is more common. But despite its prevalence, the lack of a fail-safe test is a frustration to physicians. Currently, older men at risk of prostate cancer undergo a PSA test, which detects a protein called prostate-specific antigen in the blood. Men who have elevated PSA levels, which may indicate cancer, undergo invasive biopsies but often end up not having the disease at all. Even when the biopsy finds cancer, physicians are usually unable to accurately tell how quickly the cancer will spread.

"One of the main issues with prostate cancer is trying to distinguish aggressive prostate cancer that goes on to metastasize from the slow-growing version of the disease, and what we end up doing as physicians is overtreating our patients because we can't distinguish between them," Chinnaiyan said.

Given the risks and side effects of biopsies — which range from infection to impotence — an accurate diagnostic tool for physicians as straightforward as a urine test "would be, well, wonderful," says Cory Abate-Shen, a professor at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons who authored a commentary accompanying the paper for Nature. "But that's something that will require large clinical trials to develop."

The Nature study focused on one particular metabolite, sarcosine, that was often found at elevated levels in samples taken from patients with advanced prostate cancer but was present in lower levels in samples of healthy tissue. According to the study, scanning for sarcosine proved a more accurate mode of cancer detection than scanning for the PSA protein.

"We don't even know that sarcosine is the most promising metabolite," says Michael Shen, also a professor at Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons, who co-authored the Nature commentary with Abate-Shen, his wife. "It's the one they focused on. There are other metabolites identified in their study that could easily be as interesting [as] or more interesting [than] sarcosine. So it would be very promising to look at the predictability of these individual metabolites, but also their combination."

Warning that their work needed far more investigation, the researchers also raised the possibility that sarcosine could be a "therapeutic target" that might one day offer an effective treatment of the disease. In laboratory tests, they found that adding sarcosine to prostate cells caused benign cells to become cancerous and invasive. The researchers hope that drugs that stop sarcosine from working could effectively contain prostate cancer and maybe even have implications for other cancer treatments.

In an interview with the newspaper the Guardian, Christopher Beecher, a co-author of the study, said, "This is the molecule that the cancer cells use when they want to spread. If it turns out to be involved in metastasis in other cancers, then this discovery will be huge."